Overview

Collapse

When we initiated this project at the start of 2023, a growing chorus of voices was mobilizing in favor of stronger and, importantly, ex ante or premarket regulatory scrutiny for artificial intelligence. Taking time and space to read and think deeply to arrive at viable answers seemed well worth doing. As we write this executive summary in July 2024, enacting premarket enforcement of any kind seems like a distant prospect: Why, amid these headwinds, read up on lessons from the Food and Drug Administration, one of the most regulated industries in the US?

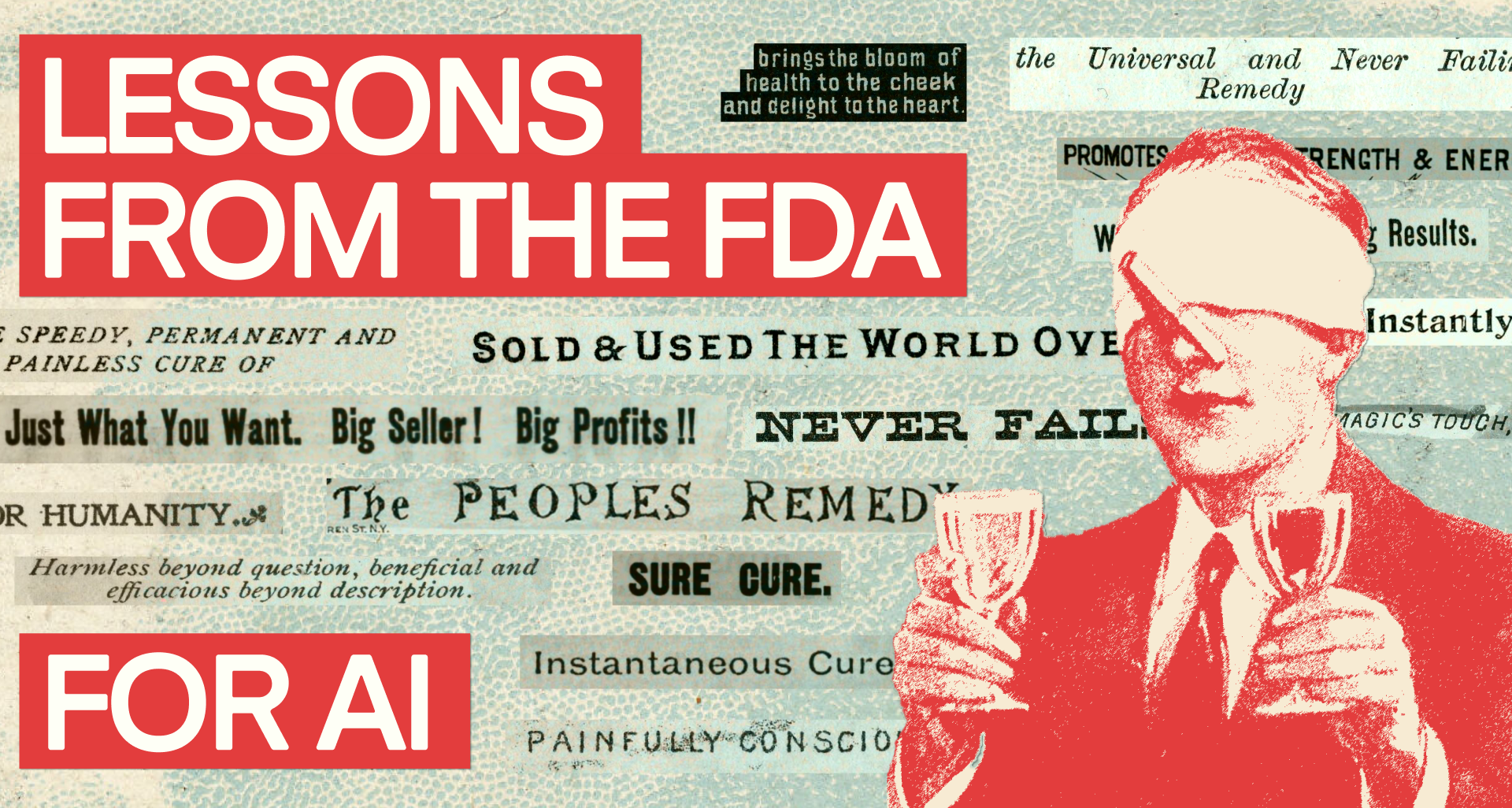

As the report that follows illustrates, the example of the FDA is most instructive not as a road map for how to approach AI, but as a set of lessons explaining why sound ex ante regulation, attuned to an evolving market and its products, can create significant benefits for both the industry and the public. The question at hand is not whether we need an “FDA for AI,” since that crude formulation will inevitably lead to unhelpfully vague answers. Rather, how the FDA transformed the pharmaceutical sector in the United States, from a domain of snake oil salesmen and quack doctors to a market that produces lifesaving drugs that are tested rigorously enough for people around the world to travel to the US just to obtain them, holds key insights for regulatory debates on AI.

DOWNLOAD THE REPORT

How to Read This Report

This report is divided into four sections. Section 1 outlines the key features of the FDA and briefly summarizes its development since the emergence in the late nineteenth century of the earliest pharmaceutical regulation in the US.

Section 2 provides an overview of the FDA’s main regulatory functions for pharmaceuticals, grouping them into three categories. In this section we describe in detail how the FDA discharges these functions and suggest how they could work for AI, surfacing areas of difficulty and complexity.

Section 3 outlines three crosscutting lessons from the experience of the FDA’s regulation of pharmaceuticals. Rather than homing in on specific functions like Section 2, it looks at how these functions interact to produce particular outcomes in the sector.

Section 4 discusses four practical challenges for implementing FDA-style interventions in AI: establishing the correct bounds of the AI market; providing AI regulators with the necessary powers to shape industry practices; overcoming legal challenges to the exercise of these powers; and avoiding industry capture.

At the end of the report we offer a glossary of key terms and appendices with information on how AI is regulated today and a detailed mapping of AI regulatory powers against those of the FDA.

Table of Contents

Collapse

Conclusion

Let’s return to the question that prompted this deliberation in the first place: Do we need an FDA for AI? Many of those who participated in the conversation arrived at the answer, “No, at least not in that exact form.” But valuable lessons were derived from deliberating deeply on the history and regulatory functioning of a single agency, considering AI governance not from the perspective of the current status quo but instead thinking through what AI might be if regulated differently. To this end, we landed on a set of concrete takeaways, highlighted above in the executive summary, as well as a number of points that will require further deliberation.

In this report, we’ve sought to “show our work” so that others might be able to learn from, and build upon, our conversation. It’s worth reiterating that the group did not seek to achieve consensus or any clear set of findings, nor did we arrive at these things. Instead, we engaged with the intent to have a grounded and deliberative conversation, siloed from the impetus to arrive at quick answers or to press for what’s immediately possible. By muddling through, we aim to get closer to the question that should be at the heart of any conversation about AI governance: What world do we want to live in, and what role should AI play in it?

Acknowledgments

Written by Anna Lenhart and Sarah Myers West, with contributions from Matt Davies and Raktima Roy. Anna’s contributions were made while a Visiting Fellow in Fall 2023/Winter 2024

We’re grateful to those who participated in deliberation on these issues. While this report offers highlights, the group did not always arrive at consensus, and individual findings have not been, and should not be, attributed to any specific individual. Participants in the conversation included Julia Angwin, Miranda Bogen, Julie Cohen, Cynthia Conti-Cook, Matt Davies, Caitriona Fitzgerald, Ellen Goodman, Amba Kak, Vidushi Marda, Varoon Mathur, Deb Raji, Reshma Ramachandran, Joe Ross, Sandra Wachter, Sarah Myers West, and Meredith Whittaker.

We’re particularly grateful to our advisory council members: Hannah Bloch-Wehba, Amy Kapczynski, Heidy Khlaaf, Chris Morten, and Frank Pasquale, and our Visiting Policy Fellow Anna Lenhart.

The deliberation was facilitated by Alix Dunn and Computer Says Maybe, with support by Alejandro Calcaño Bertorelli.

Design by Partner & Partners.

Copyediting by Caren Litherland.

This project was supported by a grant from the Open Society Foundations.

Further Reading

The following publications enriched our conversation; we recommend them as generative starting points for those who want to go further.

- Gianclaudio Malgieri and Frank Pasquale, “From Transparency to Justification: Toward Ex Ante Accountability for AI,” Brooklyn Law School, Legal Studies Paper No. 712, Brussels Privacy Hub Working Paper, No. 33, May 3, 2022, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4099657.

- Merlin Stein and Connor Dunlop, Safe before Sale: Learnings from the FDA’s Model of Life Sciences Oversight for Foundation Models, Ada Lovelace Institute, December 13, 2023, https://adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/safe-before-sale.

- Julie E. Cohen, Brenda Dvoskin, Meg Leta Jones, Paul Ohm, and Smitha Krishna Prasad, “Regulatory Monitoring in the Information Economy: Preliminary Concept Paper,” Institute for Technology Law and Policy, Georgetown Law School, October 23, 2023, https://www.law.georgetown.edu/tech-institute/wp-content/uploads/sites/42/2023/10/10232023-Draft-Regulatory-Monitoring-Concept-Paper-1.pdf.

- Andrew Tutt, “An FDA for Algorithms,” Administrative Law Review 69, no. 1 (March 15, 2016), https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2747994.

- Daniel Carpenter, Reputation and Power: Organizational Image and Pharmaceutical Regulation at the FDA (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010), https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691141800/reputation-and-power.

- Amy Kapczynski, “Dangerous Times: The FDA’s Role in Information Production, Past and Future,” Minnesota Law Review 102 (July 2018), https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr/130.