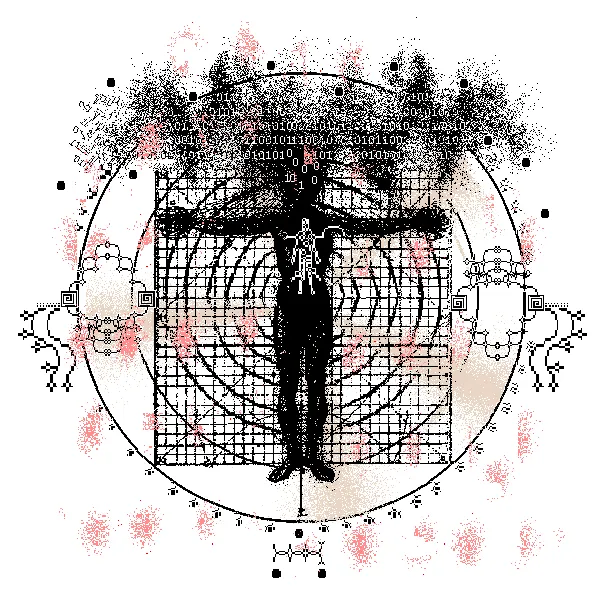

Illustration by Somnath Bhatt

Beyond Human-centrism in Olga Tokarczuk’s Ex-centrum Project

A guest post by Tomasz Hollanek. Tomasz is a PhD researcher at the University of Cambridge, working at the intersection of design theory, technology ethics, and critical AI studies. Twitter: @tomaszhollanek

This essay is part of our ongoing “AI Lexicon” project, a call for contributions to generate alternate narratives, positionalities, and understandings to the better known and widely circulated ways of talking about AI.

In late 2020, the presidency of the Council of the European Union (EU) released its conclusions on artificial intelligence and human rights. In contrast to the American and Chinese approaches, this effort formalizes what has been dubbed as “a third way” for artificial intelligence — tech regulation that prioritizes shared “European values.” The EU document focuses on the “underlying idea of human dignity” as the key element of a “human-centric approach to AI.” While it states that AI-based solutions can “perpetuate and amplify discrimination, including structural inequalities,” it also notes that “one Member State continued to object to the use of the term ‘gender equality’” in the final draft. This dissenting voice, it was later reported, was that of Poland. The country’s Permanent Representative to the EU confirmed that Poland had refused to use the proposed term because “the meaning of ‘gender’ is unclear; the lack of definition and unambiguous understanding for all member states may cause semantic problems.” Behind the semantics, however, lurks the ideological imperative: since their rise to power in 2015, the politicians affiliated with the ultra-conservative ruling party have used the concept of gender as a proxy for women’s reproductive rights and LGBTQ+ rights, and demonized it as a “synonym for chaos and instability, as well as for the colonisation of Poland by the West.” Having pushed through a near-total ban on abortion and openly dismissed LGBTQ+ rights as “a foreign ideology,” Poland’s leaders objected to the use of the term “gender” in the AI-related EU document in an effort to realize their anti-feminist politics.

Addressing the key ethical and social challenges posed by AI not only requires that we account for the impact that wider cultural contexts have on how technologies are conceived, developed, and regulated, but also that we strive to transform those contexts. Rather than examine how the Polish “culture wars” influence AI policy and development in Poland (and by extension, in the EU), we might want to ask: what would it take to stage a radical epistemological reorientation in thinking about the future of technology — in Poland, a post-communist state, a stronghold of Catholicism, and beyond? How can local communities of activists, designers, and creators work towards social and environmental justice and bring minority perspectives to the fore in an unfavorable political climate? And how can we relate such attempts to the ongoing debate on the future of AI?

For the purpose of this essay, I focus on the example of the Nobel-winning Polish writer Olga Tokarczuk and her Ex-centrum Project: a collaborative conceptual effort aiming to reframe the debate about the future in Poland so that it is guided by what she calls ex-centric perspectives. Tokarczuk’s ex-centricity echoes other calls to revise (or abandon) Western- and anthropocentric views of progress, but is a contextually radical project and, as such, constitutes an urgently needed provocation to reconsider what kinds of futures we deem desirable — and, indeed, who constitutes the “we.” Thinking about “the third way” for artificial intelligence in the EU, and the attempts to translate “European values” into AI regulation, ex-centricity serves as a reminder that “dignity” has been ascribed differently to different entities; and that to fully realize the goals of social and environmental justice, we must become aware of and reform the epistemological frameworks we rely on in the process — as it is these very frameworks that may lie at the root of exclusionary practices.

Tokarczuk won the 2018 Nobel Prize in Literature for her “narrative imagination that with encyclopedic passion represents the crossing of boundaries as a form of life.” This was met with mixed reactions in her home country: previously, the writer had been branded a “traitor” by far-right nationalists for uncovering, in her fiction, the “dark areas” of Polish history that, she argues, include acts of ethnic violence and colonization. Although the question of non-human intelligence, as well as the theme of scientific discovery feature in her work, Tokarczuk has not expressly written about artificial intelligence. It is her vision for a reformed futurology that makes Tokarczuk an unlikely, however significant, Polish voice in the debate on what it means to critically re-imagine the future of radical technological and environmental change.

Tokarczuk introduced the theory of ex-centricity in her Nobel lecture (“The Tender Narrator”), and expanded upon it in a follow-up collection of essays (published in Poland under the same title in late 2020). Ex-centricity translates to “abandoning the ‘centric’ point of view, […] moving beyond well-known areas, domains agreed upon by communal patterns of thought, rituals, and stabilized worldviews.” By postulating a comprehensive re-thinking of who gets to remain at the broadly understood “center” — of politics, knowledge-production, or technological development — in times of change, ex-centricity echoes other calls for destabilizing anthropo- and Western-centric points of view. It is the questioning of the Enlightenment tradition that Tokarczuk gestures towards, that makes ex-centricity a contextually radical and urgently needed project. Ex-centricity is a local iteration of an epistemological reorientation that the present of rapid technological development and climate change demands of us: a method for renegotiating who is — and who should be — the “we” of design in the age of artificial intelligences and natural disasters.

Ex-centricity has already had an extensive impact on public discourse in Poland. Most recently, her theory has been labelled as “anti-rationalist,” “anti-academic,” and “intellectual nonchalance” by Roman Kuźniar, a leading Polish political scientist. It is true that ex-centricity prioritizes deep relationality, rather than rationalism, as it employs what Tokarczuk calls tenderness as a primary way of knowing and representing the world: “the art of personifying, of sharing feelings, and thus endlessly discovering similarities, […] a way of looking that shows the world as being alive, living, interconnected, cooperating with, and codependent on itself.” We could think of Tokarczuk’s theory as a homegrown Polish relational ethics — even if never directly framed as such.

More and more researchers of AI ethics and governance have started to acknowledge the value of relational ethics approaches to consider the impact that new technologies have on marginalized groups and communities, as well as the environment. Notably, Abeba Birhane recently argued that only an ethics that fully embraces relationality — seeing “existence as fundamentally co-existent in a web of relations” — can allow us to go “further than human-centered or participatory design” on a path towards social and environmental justice. Ex-centricity, as a local iteration of relational ethics, might prove more relevant to renegotiating what “human-centrism” stands for and what it should represent in the Polish context than we would have initially imagined.

Tokarczuk’s recent non-fiction work laid the groundwork for the Ex-centrum Project, launched in late 2020 in collaboration with the Polityka magazine and the Wrocławski Dom Literatury (Wroclaw House of Literature). The Project involved a range of Polish thinkers, academics, and artists that Tokarczuk invited to coin new terms for a lexicon of “ex-centric content” — not so much to describe, as to shape what is yet to come. The writer’s own contribution to Ex-centrum is ognosia, or what she defines as:

“a narrative-oriented, ultra-cohesive cognitive process that, by reflecting objects, situations, and phenomena, tries to organize them into a higher, interdependent significance. […] Ognosia focuses on non-causal, extra-logical chains of events, preferring the so-called welds, bridges, refrains, synchronicities. […] Sometimes, it is considered an alternative religious position, seeking the integrating power not in some sort of superior being, but rather in the inferior, “lower” beings, the ontological pittance.”

The inaptitude for ognosia, Tokarczuk argues, manifests itself in the inability “to see the world as an integral whole, in seeing everything as separate.” Responsibility, she claims, is conditional on recognizing ourselves as nodes of this complex system. If responsibility proceeds from acknowledging complexity and interdependence, it is ognosia, according to Tokarczuk, that we should strive to develop to do better in the future.

For some Polish academics, Tokarczuk’s proposition seems too literary to constitute a coherent epistemological program and, at the same time, too irresponsibly anti-scientific to be dismissed as an artistic intervention. For others, especially the younger generation of activists, Ex-centrum appears far too elitist, “marked by some sort of paternalism,” to be satisfactorily revolutionary. They claim that in its initial stage, the Project included well-known representatives of the intellectual elite, rather than truly ex-centric perspectives, failed to accommodate for the voice of the youth, and, for now, amounts to nothing more than a purely theoretical exercise. Based on those contrasting responses, we might get the impression that Tokarczuk’s Ex-centrum epitomizes the middle ground, the safe ‘center’ that it so vehemently denies.

In reality, Tokarczuk’s work is neither anti-scientific, nor boringly conformist. Perhaps it cannot easily and immediately translate into a broad-ranging social action, but its relevance — and reformatory potential — is deeply contextual, contingent on the political situation in Poland. As the EU pushes forward with its AI policy agenda, aiming to preserve the idea of “human dignity” in the age of advanced technological development, and as Poland’s government officials push back with their anti-feminist and homophobic rhetoric that denies women and LGBTQ+ rights as human rights, Tokarczuk pushes for a reform of the epistemological frameworks that we rely on to determine who — and what — counts as worthy of dignity.