Illustration by Somnath Bhatt

Naming, Categorizing, and New Futures for AI

This is a guest post by Yung Au. Yung is a doctoral researcher at the Oxford Internet Institute (OII) and a Clarendon Scholar. Her research explores (re)coloniality of tech, surveillance, and verticalities. Twitter: @a_yung_

This essay is part of our ongoing “AI Lexicon” project, a call for contributions to generate alternate narratives, positionalities, and understandings to the better known and widely circulated ways of talking about AI.

What would computing be like as an electric brain, a little thunder, and a little flesh? Or a river, electrified? Perhaps as meat and skull and a drizzle of rain?

In Cantonese (廣東話),¹ terms are composed of sets of characters, where each individual character and its components has meaning. For example, in English, radio receivers are named after their function of extracting information from radio waves. In Cantonese however, ‘radio receivers’ (收音機) translates directly to a “sound-receiving machine” due to its function of one-way reception whereby we can hear, but not interact. Likewise, in Cantonese, telephone (電話) translates as “electric speech.” Television (電視) means “electric sight.” The computer (電腦) is an “electric brain,” and the internet (電腦網絡) is then “a network of electric brains.”

The computer is not, of course, a brain, and this particular imaginary is not necessarily helpful for examining today’s computing worlds. However, these terms do help put into perspective the shifting meanings, central concepts, and unifying ideas that underlie our thinking around computers and AI. The vocabularies we use to orient ourselves and to understand technologies are not mere coincidence or quirk but are instead, continually adapted including to and from scientific communities, corporate entities, and the public sphere, shaping in part, our ideas of what these technologies are and can be.[1]–[3]

For example, by name, the telephone, television, and computer are grouped together in Cantonese by a common undercurrent that runs through them: electricity. The English counterparts however, signals more of a discontinuity between telephone/television and the computer — where the computer is suddenly less about the “tele,” a prefix that calls attention to the distance travelled by the information being transmitted.²

The work of defamiliarizing words, categories, and what we think of as core is useful for rethinking the catch-all phrase of ‘artificial intelligence.’ As Bowker and Star argued, “to classify is human” [4]: classification is a way of parsing our impossibly complex world into useful and comprehensible segments — however, these analytical terrains are also contentious and unfinished projects. From the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), to the technologies of racial classification in apartheid South Africa, classifications in science and technology are not only imperfect but have sprawling consequences (ibid). This is especially the case when they become deeply embedded and yet, rendered invisible and impervious to questioning. Furthermore, in the space of the cutting-edge and the unknown, such as in the field of AI, metaphors help us grasp technologies that are particularly intangible. As Maya Indira Ganesh demonstrates, metaphors and narratives help us navigate new technologies, where phrases such as ‘data is the new oil’ contours our approach to these technologies, from its development to its governance [2]. The words and classifications that give forms to our realities, also shape and constrain our possible futures. Exactly what counts as AI, and who decides? What core elements of these technologies should we foreground? What imaginaries do we wish for these words to conjure?

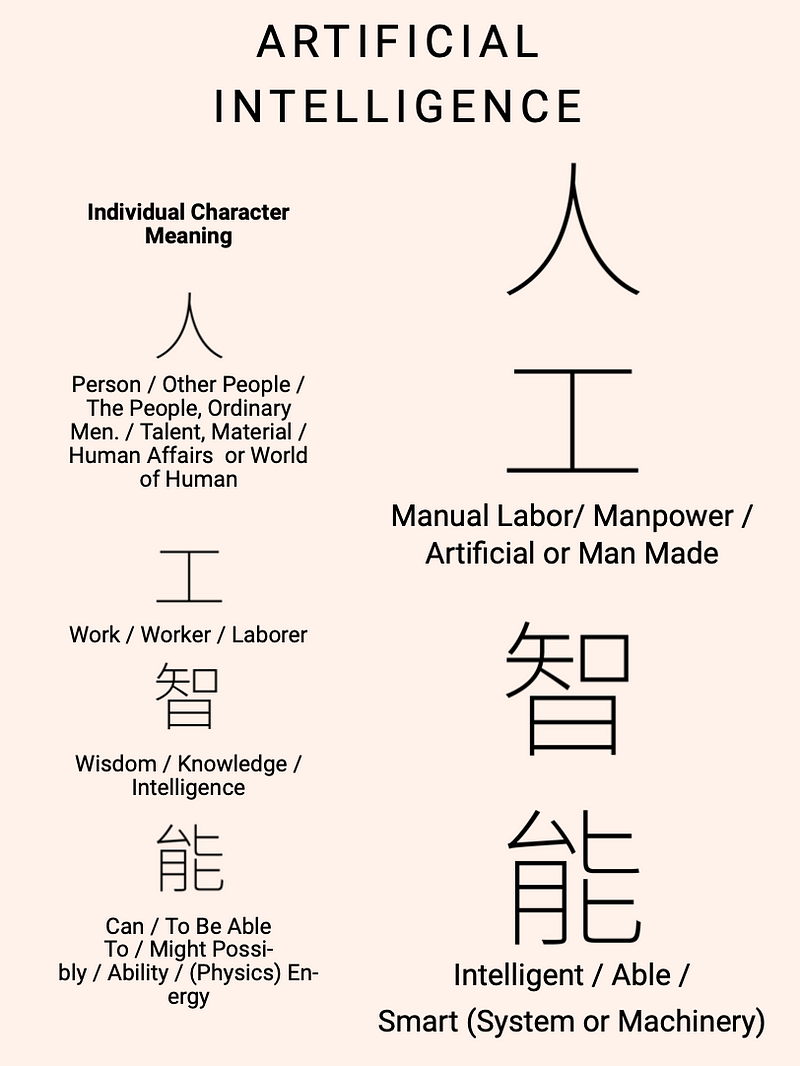

In Cantonese, the term for AI (人工智能)³ directly translates to “artificial/man-made intelligence.” However, it can also be seen as foregrounding manual labor, an aspect of these systems that is often actively obfuscated in our conceptions [5]–[7]. It is made up of four characters or two terms joined together. The first term 「人工」 has many connotations, some of which include “artificiality” but also “manpower/manual labor” and “salary.” The second term 「智能 」indicates “intelligence” (referring mostly to machines, rarely describing humans). Or it could be conceived separately, as 「人」 (person, human),「工」(work, labor), 「智」 (wisdom, resourcefulness), 「能」 (ability, degree).

Most Chinese characters have multiple meanings and connotations where terminologies do not always intentionally incorporate the many associations that exist. For example, the Cantonese term for AI may not originally have intended to foreground the importance of human labor, but it becomes a useful reminder that words have implications for how we think about things. For instance, the word “hacker” in English, which emerged from MIT in the 1960s, was derived from the word “hack” and conjures ideas of the force used to gain unauthorized access to a system — an emphasis on the process [8]. The Cantonese term for hacker (黑客) translates to “an uninvited guest,” where the unsolicited nature of this activity is emphasized.⁴ Likewise, “encryption” in English has its roots in the Greek word, kryptos, meaning “hidden” [9]. Whereas in Cantonese, encryption (加密) translates to “added security,” implying it to be another layer of security rather than a finished project in and of itself. These words recall different dimensions of the same concept, where no one single truth exists.

Today, there is growing sentiment that “AI” is a misnomer, or at least an ill fit for the many things it is meant to encompass. Critics have particularly questioned the emphasis on the “artificial” and the “intelligence,” rather than any of the countless other components that make these systems possible. What if these systems were seen as more ordinary and less exceptional; more human and less machine; more labor and less enchantment? AI can certainly be seen as an aspirational label, yet in its current usage it has been stretched so far and thin that it has become a term that simultaneously means too much and nothing at all.

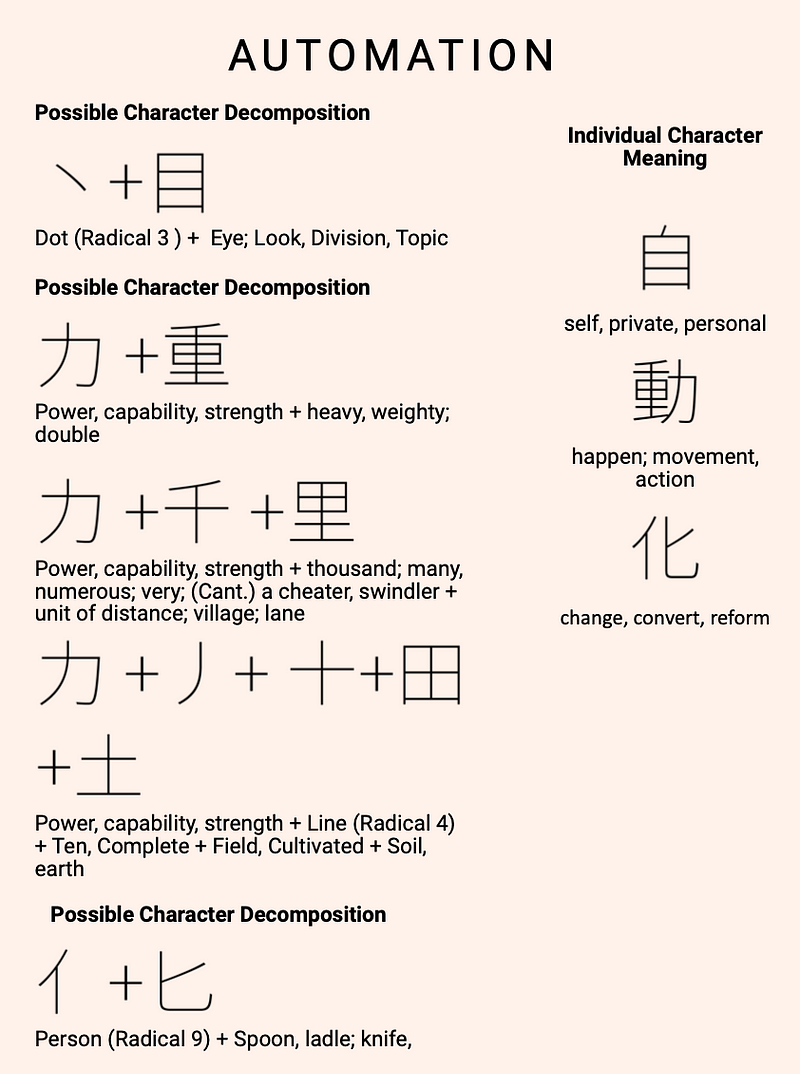

Automation in Cantonese (自動化) translates as “transition into self-operating.” The word itself has a long and convoluted history with particularly deep roots in the manufacturing context. However today, automation increasingly comes hand-in-hand with AI/ML systems, sold as a package that promises to smooth over frictions; regressions that provide a seamless trend line to disorderly plots, classifiers that sort messy datasets into workable categories. Automation here is often thought of as part of the “intelligence” these systems provide.

When affordable cameras with automatic exposure and focus settings started coming into Hong Kong’s market in the 1970–80s, they were referred to in slang as “dumb machine” (白痴機) or “silly machine” (傻瓜相機),⁵ alluding to the ease of handling and the simple design of these devices. The automation of the fiddly parts was seen as “dumbing down” the process. These cameras made photography accessible, although there was the recognition that the results could be imperfect, such as being over-exposed or being just a little out of focus. Thus despite the proliferation of these point-and-click cameras, the demand for manually operated machines remained.

Today, critical examination of automation in AI focuses on how it amplifies bias [10], inadequately replaces theory [11], or moves friction away from some people and onto others [12]. Again, the smart/dumb binary may not be the most useful frame, but there might be value in locating the starting point somewhere other than “intelligent.” Instead of assuming that machines are intelligent all the time, everywhere, there could be a recognition of the flaws of this “smoothing” process. Likewise, there could be a further disentangling of the various kinds of automation to review their relation to human labor. The etymology of automation can be traced back to Ford Motors in the US during the 1940s. Automation was meant to make something automatic or self-operating, to delegate menial labor away from humans and onto machines [13]. However, as we have seen repeatedly, AI and big data “automation” often do not miraculously remove the need for manual labor. Instead, the labor of data wranglers, labelers, trainers, micro-workers, auditors, implementers, drivers, service workers, and other essential personnel are rendered invisible [5], [7], [12], [14], [15]. What would it look like to foreground from the beginning, an awareness of where friction and labor is displaced?

It is difficult to estimate how many characters exist in the modern Cantonese vocabulary as spoken Cantonese imperfectly maps onto written forms.⁶ Written forms of Cantonese include the standard Traditional Chinese (書面語) and colloquial Cantonese (口語), with the former being used in professional settings and the latter found in informal ones. However, these situations are often ambiguous, with words weaving in and out of these contexts, and with their meanings shifting across time and space.

New terms, including slang and imported words, also often come in and out of existence, which help shape the public consciousness whether officially recognized or not. Likewise, words are also often crafted in moments of protest, where novel and reclaimed vocabularies can be a form of resistance and where subversive Chinese wordplay has existed since the early days of the Internet. The waves of unrest in Hong Kong during 2019–2020 were a particularly fertile ground for dreaming up new words and worlds. New terms were used to build movements, share inside jokes and code words, create satire, or bypass censorship and automated removals through the use of homophones [16]–[18]. It also saw the reconstitution of new Chinese characters. One example is 「自由閪」, where「「自由」is freedom and「閪」is a profanity describing female genitalia. Initially hurled as an insult by the police against protesters, many activists have since reclaimed the term through the creation a new character composed of the words “freedom” and “cunt.”⁷

It can become rather disorientating to think about the vast corpus of the Cantonese language, and the many peripheral, ephemeral words that come in and out of existence. This includes words that were only ever spoken and never written down, and the combinations of characters that never quite entered the mainstream but were nevertheless important to certain people. It can however, be freeing to remember the elasticity and flow of language, where new words, new formulations, new futures are always possible.

The act of naming something, categorizing something, and claiming authority over these processes are political acts in themselves. It is a way of remembering, planting a flag, or asserting a certain reality — but it is also not clear cut, fixed, or obvious. Names will never wholly capture our infinitely complex realities but they do encapsulate some. In the vaguely defined world of AI, words help us group comparable technologies, foreground certain dimensions, define our starting points, denote a passive or active voice, and imply partiality or neutrality. What divisions then, should we break down and what alternative arrangement should be sought anew? Do the terms that originate from Western centers of power and corporate entities align with the imaginaries we want? How can our expressions reflect the intentionality, the labor, the extraction and costs, the active choices and perpetual maintenance, the flaws, what is aspired to, and what is core? How do we ensure the words we have reflect the worlds we wish to see?

Acknowledgements: Many thanks (唔該 &多謝) to my mother and sister, Chan Tsz-Kit, Srujana Katta, Claire Robertson, Noopur Raval and Luke Strathmann for their musings, comments and edits on this piece and beyond.

Footnotes:

[1] Throughout the piece, Cantonese terms are broken down into their components and translated, however these translations do not necessarily reflect the best translation or any mainstream interpretation of a term; instead, they merely offer one of the manifold ways to look at these components in order to play with meaning and interpretation, to suggest alternatives, to break down and open up possibilities of putting our world into words.

[2] Any word has multiple histories. There are thus multiple potential explanations for how we landed on these terms today. The English words for telephone (n), television (n), and computer (n) all predate the modern form of these inventions which we are familiar with.

For instance, usage of the word telephone can be traced back to 1835 from the French word téléphone (c. 1830) coined by Jean-François Sudré but in reference to a different system that sought to convey words over distance through the use of musical notes. This system never took off in the end and the modern telephone commonly attributed to Alexander Bell was only patented decades later in 1876. Likewise, usage of the word television can be traced back to 1907 as a theoretical concept for transmitting moving images over telegraph or telephone wires (alternative terms for this were telephote in 1880 and televisa in 1904) although the first public demonstration of the modern television was only done in 1927 by the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T). The word, computer, curiously has the longest history, dating back to 1640s referring to “one who calculates” despite the modern computer being the youngest invention among the three if we take Turing’s conception of the modern computer in 1936 as the starting point.

The Chinese terms likewise traverse complicated terrains. The word for telephone (電話) was imported from a Japanese term that was created during the 19th century Meiji restoration period and is part of what are called “wasei-kango,” Japanese-made Chinese words, which were influenced by trade and political relations, but also Japanese occupation over Chinese and Taiwan territories during the 19th and 20th century. Certain Japanese words related to electricity are also, in turn, influenced by Dutch through the colonial projects of the East India Company.

Many of these inventions also had multiple competing terms in Chinese. For instance, another term for telephone was loaned phonetically from English as 德律風 (mandarin: délǜfēng; the characters itself does not mean anything) during the 1920s and was widely used in Shanghai. Eventually the current word for telephone (電話), which is constructed with semantically relevant Chinese characters, became more prevalent over time. The different formulations around these technologies shaped a myriad of sayings and ways of thinking around these inventions. A small example is a Cantonese slang phrase related to telephone, 煲電話粥 (directly translated as “boiling electric speech congee”) which is in reference to having long phone calls.

[3] There are some uncertainties surrounding the origins of the term 人工智能 in the Chinese context where there were various avenues of import of the term, AI which was created in the US in the 1950s. Competing terms here included terms such as “機器思維” (“machine” and “thinking”) in the 1970s. Likewise, there are parallels in the Japanese term for AI although notably, while the Chinese term uses “智” (wisdom; resourcefulness; wit), the Japanese term uses “知” (know; knowledge; inform) which have different implications of intelligence. Throughout its history and up till today, the usage of the words “人工” and “智能” remains debated. See further readings here:

童天湘 Tong Tianxiang.“關於“機器思維”問題 — 國外長期爭論情況綜述 on the Issue of “Machine Thinking” — an Overview of the Long-Term Debate Abroad.” Social Sciences Abroad, 1978–05–01.

陳步 Chen Bu.“人工智能問題的哲學探討 a Philosophical Exploration of the Problem of Artificial Intelligence.”Philosophical Researche, 1978–11–27.

黃欣榮 Huang Xinrong. “人工智能熱潮的哲學反思 Philosophical Reflections on the Upsurge of Artificial Intelligence.” 上海師範大學學報(哲學社會科學版)Journal of Shanghai Normal University(Philosophy & Social Sciences Edition) 47, no. 4 (2018): 34–42, pp35–6

李國山 Li Guoshang. “維特根斯坦之錘:敲敲打打為哪般? — 試論維特根斯坦與人工智能哲學 Wittgenstein’s Hammer: What’s the Point of Tapping? -Wittgenstein and the Philosophy of Artificial Intelligence: 首屆全國人工智能哲學與跨學科思維論壇 the First National Forum on Philosophy of Artificial Intelligence and Interdisciplinary Thinking.” 天津 Tianjin.

[4] This is an example of phonosemantic matching where English neologisms are translated into Chinese where both the meaning and sound of the neologism are taken into account in the creation of a term (黑客 is pronounced hak1 haak3 in Cantonese)

[5] The direct translation of this would be “foolish melon machine” where there is seemingly an element of endearment to this term. These terms are still sometimes used. In particular, Diao and Ye (2008) argued that the word 傻瓜 (foolish/silly) which used to be a derogatory word has now been repurposed to mean something that is “conveniently handled or operated”, “easy to use”, “easy to understand”. This word pairing is also seen in 傻瓜洗衣機 (“foolish” “washing machine” — an automatic washing machine) and 傻瓜電腦 (“foolish” “computer” — an easy-to-operate computer). Read more:

Diao and Ye (2008). “Two Great Transfers of Word Emotive Overtones in Modern Chinese”. Macrolinguistic 2(2):89–104.

[6] This is known as the “linguistically dual nature” of Cantonese (雙層語言), “bi-literacy but tri-lingualism” (兩文三語), or a particular form of diglossia

[7] See Hanzi Maker by The Future of Memory Team (Qianqian Ye and Xiaowei Wang) for a handy tool that helps you create new words using Chinese (simplified Chinese) https://thefutureofmemory.online/hanzi-maker/

References:

[1] S. Jasanoff and S.-H. Kim, Dreamscapes of modernity: Sociotechnical imaginaries and the fabrication of power. University of Chicago Press, 2015.

[2] M. I. Ganesh, “The Poetics and Politics of AI Metaphors,” presented at the Mutating Hazards: New Threats and Injustices in AI, CTM Festival 2021, Jan. 22, 2021, [Online]. Available: https://www.ctm-festival.de/festival-2021/programme/schedule/event/mutating-hazards-new-threats-and-injustices-in-ai-982. See also, A is for Another,, Lisa Gitelman’s book “Raw Data is an Oxymoron”, and Ifeoma Ajunwa on “The ‘black box’ at work” for further discussions on this.

[3] T.-H. Hu, A Prehistory of the Cloud. MIT press, 2015.

[4] G. C. Bowker and S. L. Star, Sorting things out: classification and its consequences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999.

[5] M. L. Gray and S. Suri, Ghost Work: How to Stop Silicon Valley from Building a New Global Underclass. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019.

[6] M. Hicks, Programmed inequality: How Britain discarded women technologists and lost its edge in computing. MIT Press, 2017.

[7] L. Irani, “The cultural work of microwork,” New Media & Society, vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 720–739, May 2015, doi: 10.1177/1461444813511926.

[8] “The History of the Word ‘Hacker,’” Deepgram, Feb. 22, 2019. https://deepgram.com/blog/the-history-of-the-word-hacker-2/ (accessed Apr. 20, 2021).

[9] “encrypt | Origin and meaning of encrypt by Online Etymology Dictionary.” https://www.etymonline.com/word/encrypt (accessed Apr. 26, 2021).

[10] J. Buolamwini and T. Gebru, “Gender Shades: Intersectional Accuracy Disparities in Commercial Gender Classification,” in Conference on Fairness, Accountability and Transparency, Jan. 2018, pp. 77–91, Accessed: Jan. 11, 2021. [Online]. Available: http://proceedings.mlr.press/v81/buolamwini18a.html.

[11] danah boyd and K. Crawford, “Critical Questions for Big Data,” Information, Communication & Society, pp. 662–679, May 2012.

[12] R. Qadri, “Delivery Platform Algorithms Don’t Work Without Drivers’ Deep Local Knowledge,” Slate Magazine, Dec. 28, 2020. https://slate.com/technology/2020/12/gojek-grab-indonesia-delivery-platforms-algorithms.html (accessed Jan. 13, 2021).

[13] “Automation | Origin and meaning of automation by Online Etymology Dictionary.” https://www.etymonline.com/word/automation (accessed Apr. 25, 2021).

[14] A. Casilli and J. Posada, “The platformization of labor and society,” Society and the internet: How networks of information and communication are changing our lives, pp. 293–306, 2019.

[15] S. Amrute and L. F. R. Murillo, “Introduction: Computing in/from the South,” Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience, vol. 6, no. 2, 2020.

[16] T. Sia, Too Salty Too Wet 更咸更濕. Speculative Place, 2021.

[17] M. Hui, “The Cantonese words at the heart of Hong Kong’s 2019 protest vocabulary,” Quartz. https://qz.com/1756464/a-guide-to-hong-kongs-cantonese-protest-slang/ (accessed Apr. 26, 2021).

[18] “Hong Kong Protest Movement Data Archive: Glossary,” Hong Kong Free Press HKFP. https://hongkongfp.com/hong-kong-protest-movement-data-archive-glossary/ (accessed Dec. 13, 2020).

Etymology and definitions from the Chinese Text Project, MDBG, Online Etymology Dictionary

Download