By Brian Merchant

INTRODUCTION

In the spring of 2019, at a live event for StrictlyVC, the technology journalist Connie Loizos asked Sam Altman how the unusually structured company he ran planned on generating revenue. “OpenAI is so amorphous,” she said. “But it is a business.” Was the aim, she wondered, to license its technology, or customize algorithms for paying clients? “How is it going to work?”1

“The honest answer is that we have no idea,” Altman replied. “We have never made any revenue, we have no current plans to make revenue, we have no idea how we may one day generate revenue. We have made a soft promise to investors that ‘once we’ve built this sort of generally intelligent system, basically we will ask it to figure out a way to generate an investment return for you.’”2

The room rippled with laughter, but Altman was serious. “It sounds like an episode of Silicon Valley, it really does, I get it, you can laugh—it’s all right,” he said. “But it is what I actually believe is gonna happen.”3

Altman’s comment is telling. It contains at least two key truths about OpenAI, the company that has spearheaded the generative AI boom now dominant in Silicon Valley and the broader business world. First, before OpenAI released DALL-E and ChatGPT, the two buzzy products that would transform it into a household name, it had no business model at all. Second, its executive leadership believed that the development of its ultimate core product, an artificial general intelligence (AGI), would solve the issue; profits would follow. This combination—a lack of a premeditated business model and an insistence on referring the public, partners, and investors to its pursuit of AGI, an aspirational technological construct, as its raison d’être, in its stead—has shaped OpenAI’s path to becoming the definitive Silicon Valley unicorn of the 2020s.

This report set out to investigate and elucidate the business models behind the generative AI companies that are drawing hundreds of billions of dollars in investment. Such models have pushed companies like Nvidia, which supplies the chips necessary for AI computation, to double and then triple its $418 billion valuation in 2022 to a historic market capitalization in excess of $3 trillion in 2024.4 It soon became clear that understanding the composition of those business models meant understanding the deployment and evolution of the concept of “AGI” as a lodestar for generative AI companies.

Any effort to understand OpenAI’s business model and that of its emulators, peers, and competitors must thus begin with the understanding that they have been developed rapidly, even haphazardly, and out of necessity, to capitalize on the popularity of generative AI products, to fund growing compute costs, and to pacify a growing portfolio of investors and stakeholders. Equally crucial is understanding how “AGI” operates in a material context, and how it serves as a driver of continued investment and enterprise sales, a marketing and recruitment tool, and a framework for bolstering the company’s influence and cultural footprint.

That OpenAI had no discernible business model upon its inception does not mean that profit potential wasn’t a consideration from the beginning. While the headlines announcing OpenAI’s launch reliably painted the project as Elon Musk and Sam Altman’s humanitarian effort to protect the world from a malignant, superpowerful AI, it was from the start a densely corporatized undertaking, established in a posh hotel in the middle of Silicon Valley with seed money from tech billionaires, Amazon, and top venture capitalists—despite being labeled a “nonprofit.”

There’s no reason to doubt that Altman was answering earnestly when he declared to Loizos that OpenAI had no business model to speak of. It wasn’t a pressing issue. Why? For one thing, this was the end of the 2010s, a decade in which the tech sector enjoyed rock-bottom federal interest rates and it was never easier for founders and startups to attract funding; as a result, much of Silicon Valley’s investor class had grown accustomed to making bets that promised scale, grandeur, and “unicorn” status over reliable marginal returns and sound business plans. In fact, we might consider OpenAI the apotheosis of a trend that rose to prominence with startups like Uber and WeWork, formed in the heady post-Web 2.0 era. It was a time when highly salable products like the iPhone and ad-based Google search ruled the tech sector, and when it was assumed that software would eat the world with such ferocity that few people worried about overhead or operating costs.

That picture had changed dramatically by the 2020s. The federal reserve began raising interest rates in December 2015—incidentally, the same month that Altman announced the launch of OpenAI—after seven years of keeping them near zero in the wake of the Great Recession.5 The hikes ended the era of free money for Silicon Valley, and investment in startups began to slow. The higher credit rates quickly made clear that tech had another issue on its hands: it hadn’t had a truly hit product category in years. Facebook, Google, and the iPhone had all risen to prominence more than a decade ago; Uber, Lyft, and other gig-economy companies were still not profitable, and a cascade of broadly hyped tech trends—crypto, Web3, the metaverse—crashed and burned in rapid succession. Waves of layoffs hit the industry in 2022 and 2023, and Silicon Valley was, for the first time in a generation, at risk of entering into a recession.

These are the conditions into which the AI boom was born. And that boom, launched by a company built on the assumptions and logics of the zero-percent-interest-rate era, with presumed access to vast stores of investment, soon acquired an urgent need for a product to sell to users and corporate clients. In the rush to capitalize on its rise to prominence, AI companies, especially OpenAI, would wield a story about a technology so powerful it would soon have a life of its own—so powerful you could simply ask it how to make more money, and it would oblige. All of this converged to give rise to the modern generative AI trend.

The business model, it could safely be assumed, would come later.

OPEN AI AND THE GENERATIVE AI BOOM

To understand the thrust and structure of the business models taking shape in the generative AI space, we need to understand OpenAI, the driving force that most—if not all—of the new companies are reacting to, emulating, or feeding off. OpenAI is at the center of nearly every conversation about the technology, both inside the industry and out. With a self-reported $3.4 billion in annualized revenue projected this year,6 it’s the largest company operating in the space, with the highest valuation: $157 billion, based on its most recent funding round.7

Meanwhile, OpenAI’s most similarly constituted competitor, Anthropic (which says it’s on track to make $850 million in revenue this year8), was founded by former OpenAI employees, as was the much-hyped “answer engine” Perplexity. Microsoft is OpenAI’s closest partner, lending it $10 billion in funds and cloud compute, and getting a ChatGPT-powered Copilot out of the deal, while Google and Facebook hastily launched product development cycles of their own in response to the shock waves sent out by ChatGPT in late 2022 and early 2023.

We lead with the case study of OpenAI, and interrogate how it’s a rather immaculate product of its time and place: unicorn-hunting-era Silicon Valley and the decade of zero-percent interest rates.

SILICON VALLEY MYTHOLOGY, DISTILLED AND ACCELERATED

“If you think about the things that are most important to the future of the world, I think good AI is probably one of the highest things on that list. So we are creating OpenAI,” Sam Altman told veteran tech journalist Steven Levy in 2015, in an interview announcing the company. “The organization is trying to develop a human positive AI. And because it’s a non-profit, it will be freely owned by the world.”9

To anyone unfamiliar with the historical context of OpenAI’s founding mission, the notion that the $157 billion company, which has raised the largest VC round in history,10 and whose revenue comes from selling enterprise software and API access to corporations like PwC, is a “nonprofit” that will be “freely owned by the world” may seem jarring. Therefore, it’s worth charting its evolution from nonprofit to very-much-for-profit—an important piece of the puzzle because this evolution is what has effectively eroded the boundary between mythology and business model.

OpenAI began as a grandiose, science fiction-adjacent, and high-concept venture whose aim was explicit in its ambitions: to ensure that superpowerful AGI was developed safely, in a way that would benefit all humanity. The purported gravity of this mission was such that, for years, it eschewed a business model altogether (an approach also subsidized by the beneficiaries of the unicorn era of heavy VC investment). As such, OpenAI’s eventual $157 billion valuation marks a milestone: It is the first modern tech giant birthed with a promise that what it was doing was so momentous that it need not consider revenue at all—it would be a nonprofit.

Silicon Valley has long had a penchant for grandiosity, but if we’re charting the ratio of its world-changing talk to demonstrable business feasibility, from, say, Apple, which helped mint the practice of cosmic sales pitches yet still sold hardware in retail shops; to Uber, whose talk of disruption was ubiquitous, whose app was popular, but whose bottom-line math was always fuzzy; to OpenAI, then perhaps we can see the moment when the cart is placed fully before the horse: when the story of a venture, the story of a new technology with commercial potential, eclipsed the need for a business model at all.

But the story starts in earnest before OpenAI is even founded, when “superintelligent AI” is a trending area of interest and concern among Silicon Valley elites11 and, as we’ll see, arguably a way for late entrants in the space to gain competitive advantage. In the 2010s, the commercial AI space was dominated by Google and Facebook, which were each investing in machine learning technologies and competing to acquire promising startups like Deepmind and to hire top talent like Geoffrey Hinton. Analysts like Musk’s biographer, Bloomberg reporter Ashlee Vance, have argued that this made Musk professionally jealous. Publicly, Musk may have worried about AI safety; privately, his concerns may have been more about missing out on a major developing tech trend and business opportunity.12 A widely documented argument between Musk and former Google CEO Sergey Brin over whether AI would benefit or threaten humanity is sometimes cited as the starting point for OpenAI.13 Yet it is important to note that Musk had personal and financial reasons to oppose the commercial development of AI by Google or the other tech giants.

To understand the genesis of OpenAI, we consider the likelihood that the company was never the altruistic venture it portrayed itself as to the media—despite being formed as a nonprofit—but rather a vehicle through which Musk and Altman could achieve various personal and business objectives, including stalling Google’s progress on AI and positioning OpenAI to be a more attractive alternative in the eyes of top research talent, consumers, and thus investors.

A Timeline of Crucial Events Regarding the Formation of OpenAI, and the Influence of Musk and the Specter of “AGI” in Its Organizational DNA

2012

Elon Musk meets the founder of Deepmind, Demis Hassabis, who, according to multiple accounts, sparks his interest in AI by detailing the risks it poses to humanity.14 Musk invests $5 million in the company. Musk meets Sam Altman, then a partner at influential startup incubator Y Combinator.

2013

Google expresses interest in acquiring Deepmind. Musk discusses AI at his birthday party in Napa with Google cofounder Larry Page.15 Musk is reportedly envious of Google’s dominance in AI, and his formerly close relationship with Page is fraying. He reportedly argues that Page is not cautious enough with AI; the two have a falling-out. Musk attempts to dissuade Hassabis from selling to Google.16

2014

Google announces it has acquired Deepmind for $500 million.17 Musk makes headlines by declaring AI to be “our biggest existential threat” during an interview at MIT, among the first of his documented statements about the power of malign AI.18 Altman, now president of Y Combinator, begins exchanging emails with Musk about AI.

2015

“Development of superhuman machine intelligence,” Altman writes on his personal blog in February, “is probably the greatest threat to the continued existence of humanity.”19 Altman emails Musk in May proposing they start an AI lab together. “Thinking a lot about whether it’s possible to stop humanity from developing AI. I think the answer is almost definitely not. If it’s going to happen, it seems like it would be good for someone other than Google to do it first.”20 Musk and Altman organize a dinner at the Silicon Valley dealmaking hot spot the Rosewood Hotel with leading AI researchers and founders to discuss starting that lab. Musk leads an open letter calling for a ban on AI weapons.21 Altman and Musk recruit Stripe CTO Greg Brockman and notable AI researcher Ilya Sutskever, among others, and begin forming OpenAI.

Nov. 2015

In an email discussing the announcement of OpenAI, Elon Musk writes: “I’d favor positioning the blog to appeal a bit more to the general public—there is a lot of value to having the public root for us to succeed—and then having a longer, more detailed and inside-baseball version for recruiting, with a link to it at the end of the general public version.”22

Dec. 2015

OpenAI publicly launches with a stated mission of developing AI “in a way most likely to benefit humanity as a whole,” to widespread media interest.23

From the outset, while publicly positioned as a nonprofit, OpenAI was structured and anticipated by its founders as having the potential for profit, or at least the potential to wield influence. While there was no business model, OpenAI served a distinct business purpose: suppressing Musk’s competitors and offering the ambitious Altman a bridge to Musk—one of the wealthiest and most influential figures in Silicon Valley—and his circle of allies.

One lens through which to view the emergence of “AGI” or “human-level AI” or “superintelligent AI” as a widespread discussion point is thus as the result of a business and retaliatory tactic leveraged by Musk and embraced by Altman, as an effort to lash out against or even attempt to suppress development and/or deployment of commercial AI products by Google in particular. This positioning also benefits the institution or company whose public aim is to develop and deploy AI “safely”—which happens to be OpenAI’s founding mission.

This tactic may have proved successful. Google, after all, had developed many key frameworks and technologies, like TensorFlow, an open source machine learning software library; and the “transformer” that gives the General Pre-Trained Transformer in ChatGPT its name. It had a yearslong head start on OpenAI on LLM technology: in 2013 Hinton brought his machine learning acumen to Google, which acquired DeepMind the following year, introduced LaMDA in 2020, and developed Bard and Gemini in 2023. In 2016, just months after becoming CEO, Sundar Pichai announced that Google would become “an AI-first” company.24 Yet OpenAI ate its lunch.

This is partly because Google had stepped on a series of rakes in its commercial AI development, gaining a reputation for releasing “creepy” products and silencing critical AI researchers, both internally and externally. In 2020, the company pushed out star AI ethicist Timnit Gebru after preventing her now-seminal paper “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?” from being published.25 In 2022, it fired software engineer Blake Lemoine, who went public with his fears that Google’s internal chatbot products had become sentient.26 As a result, the company did not release a similar chatbot product to OpenAI, in part out of fear that such a product would result in public anxiety and bad press.27 Google issued a “code red” internally after OpenAI’s ChatGPT exploded in popularity at the end of 2022, and raced to catch up by releasing a competing product. There is also a lesson here about the importance of developing a corporate narrative: by the mid 2010s, Google, the object of public ire and rounds of bad publicity for releasing Google Glass and for revelations that it crawled your inbox to improve ad suggestions (both of which the public felt violated privacy concerns), had a reputation for being invasive; when it released an early voice-activated AI chatbot product called Duplex, it caused controversy and backlash.28 After years of nurturing its image as concerned custodians of safe AI, OpenAI suffered little such blowback.

With this context, that OpenAI’s founding mission was guided by distinct business objectives, we can consider the nature of that founding mission—to build a safe, human-level AI that would benefit everyone—and how it evolved. Or at least, the story of that founding mission. Elon Musk certainly knew well the benefit of having a narrative behind his companies; SpaceX would catapult humanity into a multiplanetary species, Tesla was helping to save the world from climate change. OpenAI would save it from super-powerful AI. And at a time when investors were bankrolling otherwise underwater but extremely ambitious startups like Uber, Lyft, InstaCart, and WeWork—companies that lost money every year but promised massive scale and disruption—the story was crucial.

“There is a lot of value,” as Musk put it in one of his emails to fellow OpenAI founders, “in having the public root for us to succeed.”29

***

Next, we’ll examine the recent historical context of OpenAI’s founding mission, which appears so jarring now, and chart its evolution from nonprofit to very-much-for-profit. It’s an evolution that has been buffeted by low interest rates that infused the SV ecosystem with its most adventuring mindset, and eroded the boundary between mythology and business model.

FROM “SAFE AI” TO AGI — AND THE HYPE-LED BUSINESS MODEL GENESIS

When OpenAI launched, it described itself as a “nonprofit artificial intelligence research company” whose mission was “to advance digital intelligence in the way that is most likely to benefit humanity as a whole, unconstrained by a need to generate financial return.”30

Its initial financial backers included Musk,31 Altman, Brockman, Peter Thiel, LinkedIn founder Reid Hoffman, the Indian IT company Infosys, Y Combinator, and Amazon Web Services. Its stated aim was to be able to hire top AI researchers from high-paying gigs like Google—to conduct research like a nonprofit while paying for-profit salaries.

OpenAI’s launch announcement raised the alarm, once again, of an incipient superintelligent AI, though this time it referred to the concept as “human-level AI.” Its very first post declared: “It’s hard to fathom how much human-level AI could benefit society, and it’s equally hard to imagine how much it could damage society if built or used incorrectly.”32

From the outset, OpenAI’s dramatic mission struck a chord with the tech press, in no small part due to Musk’s involvement, and, to a lesser extent, Altman’s. Taking cues from the organization’s first press release and interviews with key players given at the time, the media described the project as a heroic, even utopian, effort. “Elon Musk and Partners Form Nonprofit to Stop AI from Ruining the World,” read a headline in the Verge.33 “Tech Giants Pledge $1Bn for ‘Altruistic AI’ Venture, OpenAI,” said another on the BBC’s website.34 Vanity Fair described OpenAI as “a non-profit company to save the world from a dystopian future.”35 And Levy’s interview with Altman was titled “How Elon Musk and Y Combinator Plan to Stop Computers from Taking Over.”

Altman and Musk thus imprinted onto the tech press and the general public the notion that OpenAI would be dedicated to the cause of developing a “safe” superintelligent AI, free of a profit motive.36 It made for a compelling narrative—unlike the gargantuan Google or monolithic Microsoft, here were researchers uninterested in making money but all in on protecting the world from a technology so powerful it could lead to humanity’s ruin if poorly stewarded. Altman even told Levy that OpenAI would be “open source and usable by everyone.”37 It is remarkable, with the gift of hindsight, how little Musk’s or Altman’s motives were interrogated at the time.

This also marks the early deployment of OpenAI’s key marketing terms, like “safe AI,” “open,” “beneficial to all of humanity,” and “superpowerful”—in hindsight, we can now consider these marketing terms from the outset. Especially pertinent is the shift in focus from “open source” and “safe” AI, terms handy for spinning up headlines and attracting goodwill and idealistic, talented researchers, to “creating AGI,” which would come to be central to OpenAI’s language, and which is a mission that promises a more proactive development of powerful technology—and one that might benefit your business.38

It may be useful to consider the central term of art here. Artificial intelligence was itself originally coined as a marketing phrase. “I invented the term artificial intelligence,” AI pioneer John McCarthy said in the 1973 Lighthall debate, “and I invented it because we had to do something when we were trying to get money for a summer study in 1956.”39 The term was devised, in other words, to appeal to funders. It is also worth noting that AI researchers in the 1960s and ’70s already meant “AGI” when they said “AI”—many luminaries in the field made predictions that an artificial intelligence that could do anything a human could do would emerge within a generation at the latest.40 The looseness of this terminology was capitalized on by early computer firms like IBM, which invested in the space; and was promulgated in pop culture, perhaps most famously in 2001: A Space Odyssey, which took place in the year AI scientists believed human-level AI would arise.

AI has in other words been deployed as a marketing term for decades, as computational linguistics scholar Emily Bender and others have argued at length.41 But if it is primarily a marketing term—one used to describe a category of technical sciences and product development so broad it approaches meaninglessness—then it’s also a familiar one, and one less capable of exciting the interests of investors and the public. It was in need of an upgrade—and AGI, not just artificial intelligence, but a powerful general intelligence that can do whatever a human can, fit the bill. The term “artificial general intelligence” was coined by Mark Gubrud in a 1997 paper as a means of describing an AI distinct from the narrower “expert systems” that had come to dominate the field after those earlier lofty predictions of intelligent software failed to come to pass.42 The term was revived in the 2010s.43

Eventually, OpenAI—along with much of the tech industry—would seize on the term and render it central to their marketing efforts. Here’s an overview of this evolution.

Timeline of OpenAI’s deployment of AI and AGI terms

| Dec. 2015 The company launches, describing itself as “a non-profit artificial intelligence research company. Our goal is to advance digital intelligence in the way that is most likely to benefit humanity as a whole, unconstrained by a need to generate financial return. Since our research is free from financial obligations, we can better focus on a positive human impact. “We believe AI should be an extension of individual human wills and, in the spirit of liberty, as broadly and evenly distributed as possible. The outcome of this venture is uncertain and the work is difficult, but we believe the goal and the structure are right. We hope this is what matters most to the best in the field. . . . It’s hard to fathom how much human-level AI could benefit society, and it’s equally hard to imagine how much it could damage society if built or used incorrectly.”44 | Jul. 2016 In the initial announcement detailing OpenAI’s specific goals—the first is to measure progress, the second to build a household robot, the third to build an agent with “natural language understanding,” and the fourth to have an agent “solve a wide variety of games”—the company reiterates its mission: “OpenAI’s mission is to build safe AI, and ensure AI’s benefits are as widely and evenly distributed as possible.”45 | Nov. 2016 OpenAI and Microsoft announce a deal: OpenAI will use Microsoft’s Azure cloud service for its experiments. “It’s great to work with another organization that believes in the importance of democratizing access to AI. We’re looking forward to accelerating the AI community through this partnership.”46 |

| Early 2017 According to Altman, he, Musk, and the executive leadership of OpenAI begin discussing plans to restructure the company to acquire additional funding. “We spent a lot of time trying to envision a plausible path to AGI. In early 2017, we came to the realization that building AGI will require vast quantities of compute. We began calculating how much compute an AGI might plausibly require. We all understood we were going to need a lot more capital to succeed at our mission—billions of dollars per year, which was far more than any of us, especially Elon, thought we’d be able to raise as the non-profit.”47 Elon Musk suggests folding OpenAI into Tesla, or that he have full control over a newly structured for-profit venture, with a majority stake and CEO title. OpenAI declines, and elects to install Altman as CEO.48 | Feb. 2018 OpenAI announces new investments and Musk’s departure: “We’re broadening our base of funders to prepare for the next phase of OpenAI, which will involve ramping up our investments in our people and the compute resources necessary to make consequential breakthroughs in artificial intelligence.”49 | Apr. 2018 OpenAI releases its charter, centering for the first time the term “AGI.” The charter, which still appears on OpenAI’s website today, states: “OpenAI’s mission is to ensure that artificial general intelligence (AGI)—by which we mean highly autonomous systems that outperform humans at most economically valuable work—benefits all of humanity. We will attempt to directly build safe and beneficial AGI, but will also consider our mission fulfilled if our work aids others to achieve this outcome.” The core planks of the charter include “broadly distributed benefits,” “long-term safety,” “technical leadership,” and “cooperative orientation.” The statement notes: “Our primary fiduciary duty is to humanity.”50 |

| Jun. 2018 OpenAI releases an early GPT language model.51 | Feb. 2019 OpenAI releases a research paper detailing the results of its latest text-generation model, yet allows tech reporters to demo the technology. The result is a round of PR for OpenAI that further positions AI as dangerous, and the company as an unusually ethical steward of said technology. A representative headline, from Wired, reads: “The AI Text Generator That’s Too Dangerous to Make Public.”52 The article begins: “In 2015, car-and-rocket man Elon Musk joined with influential startup backer Sam Altman to put artificial intelligence on a new, more open course. They cofounded a research institute called OpenAI to make new AI discoveries and give them away for the common good. Now, the institute’s researchers are sufficiently worried by something they built that they won’t release it to the public.” This announcement generated significantly more interest in OpenAI than any previous news cycle, besides the company’s founding. | Mar. 2019 The next month, OpenAI announces it is transitioning from a nonprofit research company into “a new ‘capped-profit’ company that allows us to rapidly increase our investments in compute and talent while including checks and balances to actualize our mission.”53 The announcement elaborates: “Our mission is to ensure that artificial general intelligence (AGI) benefits all of humanity, primarily by attempting to build safe AGI and share the benefits with the world. We’ve experienced firsthand that the most dramatic AI systems use the most computational power in addition to algorithmic innovations, and decided to scale much faster than we’d planned when starting OpenAI. We’ll need to invest billions of dollars in upcoming years into large-scale cloud compute, attracting and retaining talented people, and building AI supercomputers. We want to increase our ability to raise capital while still serving our mission, and no pre-existing legal structure we know of strikes the right balance. Our solution is to create OpenAI LP as a hybrid of a for-profit and nonprofit.”54 |

To Recap:

OpenAI publicly launched as a nonprofit with the self-described mission of developing a “safe,” “human-level,” open-sourced AI that would “benefit all of humanity,” emphasizing it had no financial incentive. Just before it announces a restructuring into a for-profit entity, OpenAI publishes a charter centering its mission as bringing about “AGI,” explicitly casting this as the primary goal. After the specter of AGI is raised, OpenAI releases to the press a text model it says is too dangerous to release to the public, taking full advantage of the social imaginary of a looming AGI. The press publicizes both the model, which is impressive, and OpenAI’s prudence in exercising caution over its own creation, making “the AI that’s too dangerous to release” a phenomenon in the tech media. Months later, OpenAI announces a $1 billion deal with Microsoft, again touting its pursuit of AGI.

| Jul. 2019 By the summer, “AGI” is being splashed in the headline of one of OpenAI’s highest-profile press releases yet. Announcing a $1 billion partnership with Microsoft, OpenAI says: “Microsoft invests in and partners with OpenAI to support us building beneficial AGI.”55 Note the language, and the shift away from centering “safety” to emphasizing the power of a (still speculative) AGI: “AGI will be a system capable of mastering a field of study to the world-expert level, and mastering more fields than any one human—like a tool which combines the skills of Curie, Turing, and Bach. An AGI working on a problem would be able to see connections across disciplines that no human could. We want AGI to work with people to solve currently intractable multi-disciplinary problems, including global challenges such as climate change, affordable and high-quality healthcare, and personalized education. We think its impact should be to give everyone economic freedom to pursue what they find most fulfilling, creating new opportunities for all of our lives that are unimaginable today. OpenAI is producing a sequence of increasingly powerful AI technologies, which requires a lot of capital for computational power. The most obvious way to cover costs is to build a product, but that would mean changing our focus. Instead, we intend to license some of our pre-AGI technologies, with Microsoft becoming our preferred partner for commercializing them. We believe that the creation of beneficial AGI will be the most important technological development in human history, with the potential to shape the trajectory of humanity. We have a hard technical path in front of us, requiring a unified software engineering and AI research effort of massive computational scale, but technical success alone is not enough. To accomplish our mission of ensuring that AGI (whether built by us or not) benefits all of humanity, we’ll need to ensure that AGI is deployed safely and securely; that society is well-prepared for its implications; and that its economic upside is widely shared. If we achieve this mission, we will have actualized Microsoft and OpenAI’s shared value of empowering everyone.”56 | Dec. 2020 OpenAI co-founder Dario Amodei leaves the company, reportedly over concerns about the Microsoft partnership. In an update announcing Amodei’s departure, Altman notes that “OpenAI’s mission is to thoughtfully and responsibly develop general-purpose artificial intelligence, and as we enter the new year our focus on research—especially in the area of safety—has never been stronger. Making AI safer is a company-wide priority, and a key part of Mira [Murati]’s new role.”57 | Jan. 2021 OpenAI releases the text-to-image generator DALL-E. The announcement states: “We recognize that work involving generative models has the potential for significant, broad societal impacts. In the future, we plan to analyze how models like DALL·E relate to societal issues like economic impact on certain work processes and professions, the potential for bias in the model outputs, and the longer term ethical challenges implied by this technology.”58 |

| May 2021 Amodei announces his new company Anthropic with a historic $124 million investment, the largest sum thus far raised for a company trying to build all-purpose AI. The company describes itself as “an AI safety and research company that’s working to build reliable, interpretable, and steerable AI systems.”59 Amodei says he aims to “deploy these systems in a way that benefits people.”60 As Anthropic becomes OpenAI’s largest non-FAANG competitor, it uses “AI safety” as a guiding principle and marketing term.61 | Apr. 2022 OpenAI releases DALL-E 2. “This is not a product,” Mira Murati, OpenAI’s head of research, tells the New York Times. “The idea is understand [sic] capabilities and limitations and give us the opportunity to build in mitigation.”62 The AI image generator is celebrated in the press.63 | Nov. 2022 OpenAI releases ChatGPT. The language in the launch announcement is more retail-oriented—the culmination, perhaps, of a yearslong marketing effort to generate interest in what is now clearly touted as a commercial product: “We are excited to introduce ChatGPT to get users’ feedback and learn about its strengths and weaknesses. During the research preview, usage of ChatGPT is free.”64 The company’s reputation as the vanguard of responsible AI development—this was the company that was built to protect humankind from malicious AI, after all—meant that the release of the product was treated with extra gravity by the press. “We are not ready,” Kevin Roose of the New York Times writes about the text-generating chatbot product.65 |

MARKETING AGI, SHIPPING COMMERCIAL AI

OpenAI launched as a nonprofit positioned to fulfill a business objective, was from the start rich with profit-making potential, and deployed marketing terms to create a narrative about its altruistic pursuit of building a “safe” “AGI.” It is immaterial whether or not the participants in this venture believe in the risks of AI—many clearly do—but these risks serve marketing purposes regardless. If an AI product may be all-powerful, it is all the more alluring to executives and managers who hope to harness it to increase productivity and save labor costs. From the start, OpenAI has positioned itself to be the only reliable steward of this dangerous AGI-adjacent technology—and so we should trust only them when the time comes to sell it.

Tracing the usage of the term “AGI” in OpenAI’s marketing materials, patterns emerge. The term is most often deployed at crucial junctures in the company’s fundraising history, or when it serves the company to remind the media of the stakes of its mission. OpenAI first made AGI a focus of official company business in 2018, when it released its charter, just after it announced Elon Musk’s departure; and again as it is negotiating investment from Microsoft and preparing to restructure as a for-profit company.

In January 2023, just over a month after the launch of ChatGPT, when the technology was still rapidly ascendent—it would be the fastest app to climb to 100 million users, according to the company—OpenAI and Microsoft announced a $10 billion partnership that OpenAI stated “will allow us to continue our independent research and develop AI that is increasingly safe, useful, and powerful.”66 There is no mention of AGI explicitly. Two months later, when ChatGPT was sufficiently publicized and perhaps even beginning to plateau in user growth, and when Microsoft had an interest in publicizing its own ChatGPT-powered products, its researchers published a paper announcing that ChatGPT 4 showed “sparks” of AGI.67

OpenAI is nearly the precise inverse of what it initially promised to be—instead of open source and nonprofit, structured to avoid any single person taking too much power over this supposedly all-powerful technology, it has evolved into a company that is highly proprietary and explicitly for-profit, with a single person, CEO Sam Altman, exerting near-total control over the operation. Yet this is little remarked upon in the media, or by business analysts, with the somewhat ironic exception of Elon Musk, who filed a suit alleging that by transitioning into a for-profit, non-open source entity, OpenAI violated the terms of his initial funding.

OpenAI burst into public consciousness and into the headlines in late 2022 after its public release of ChatGPT, which would come to be synonymous with the new booming product category of generative AI. Throughout 2023, Silicon Valley—and many other industries, led by consultancies and finance—reoriented itself around the most-hyped technology it had seen in years: chatbots, image generators, audio synthesizers, and other AI products rolled out from startups and established giants. AI became the single dominant trend in tech, and bent all other products to its arc.

Generative AI caught the public’s eye with flashy tech demos, which OpenAI executives rapidly translated into hype for the new services, and for the power of AI in general. The hype reached apocalyptic levels, replete with Altman making a tour through Washington and European capitals, apparently leading a public charge for regulation; testifying to the power of the technology; and making himself the point person for corporate AI policy. The mythology constructed since OpenAI’s founding can be seen paying dividends throughout 2023.

The AGI construct can also be used as a device for blunting scandals, or for reminding investors of OpenAI’s ultimate business objective. For instance, in May 2024, when OpenAI endured a string of its most stinging scandals—the most notable being Scarlett Johansson accusing the company of mimicking her voice without consent68—the company responded by announcing a new safety council and a new “frontier model” to help create AGI: “OpenAI has recently begun training its next frontier model and we anticipate the resulting systems to bring us to the next level of capabilities on our path to AGI.”69

By 2024, the evolution of AGI into purely a marketing term, disconnected entirely from the research sphere, was complete. OpenAI hailed the launch of an automated customer support company called MavenAGI, built with its GPT technology, on the official company website: “MavenAGI is a new software company for the AI era.”70 Over the decades “AI” had become rote, familiar, and so broadly understood as to be meaningless. AGI could be seen as a marketing-friendly reclamation of the concept to differentiate a new raft of products from a decades-old discipline.

And if AGI was the marketing driver, then generative AI was the demo ideally suited to communicate its potential. Its “magical” autogenerated images, uncanny-valley videos, and a chatbot that mimicked human user behavior in its presentation (with its flickering cursor and sentences being typed out in real time as if by a supersmart person behind the scenes) gave the impression that this was humanity, augmented. The success of the DALL-E and ChatGPT demos meant that the early business interest would be in automating text, code, and image generation—and in automating creative labor. It would incentivize AI companies to shape their business models to capitalize on this interest, and to conform their pursuits of enterprise deals to this narrative.

OpenAI helped construct an imaginary where an AGI of great power looms on the horizon—one that can do anything a human can, at least in the digital world—and offered a suite of demonstrations as evidence. For all the wonder they sparked, the clearest path to a business model seemed to be articulating the capacity for AGI to automate human labor. Indeed, that was how it was redefined in OpenAI’s 2018 charter: AGI remains defined by OpenAI as “highly autonomous systems that outperform humans at most economically valuable work.”71 While it was still unclear as to what most generative AI companies’ precise business models would be, investment was unleashed nonetheless.

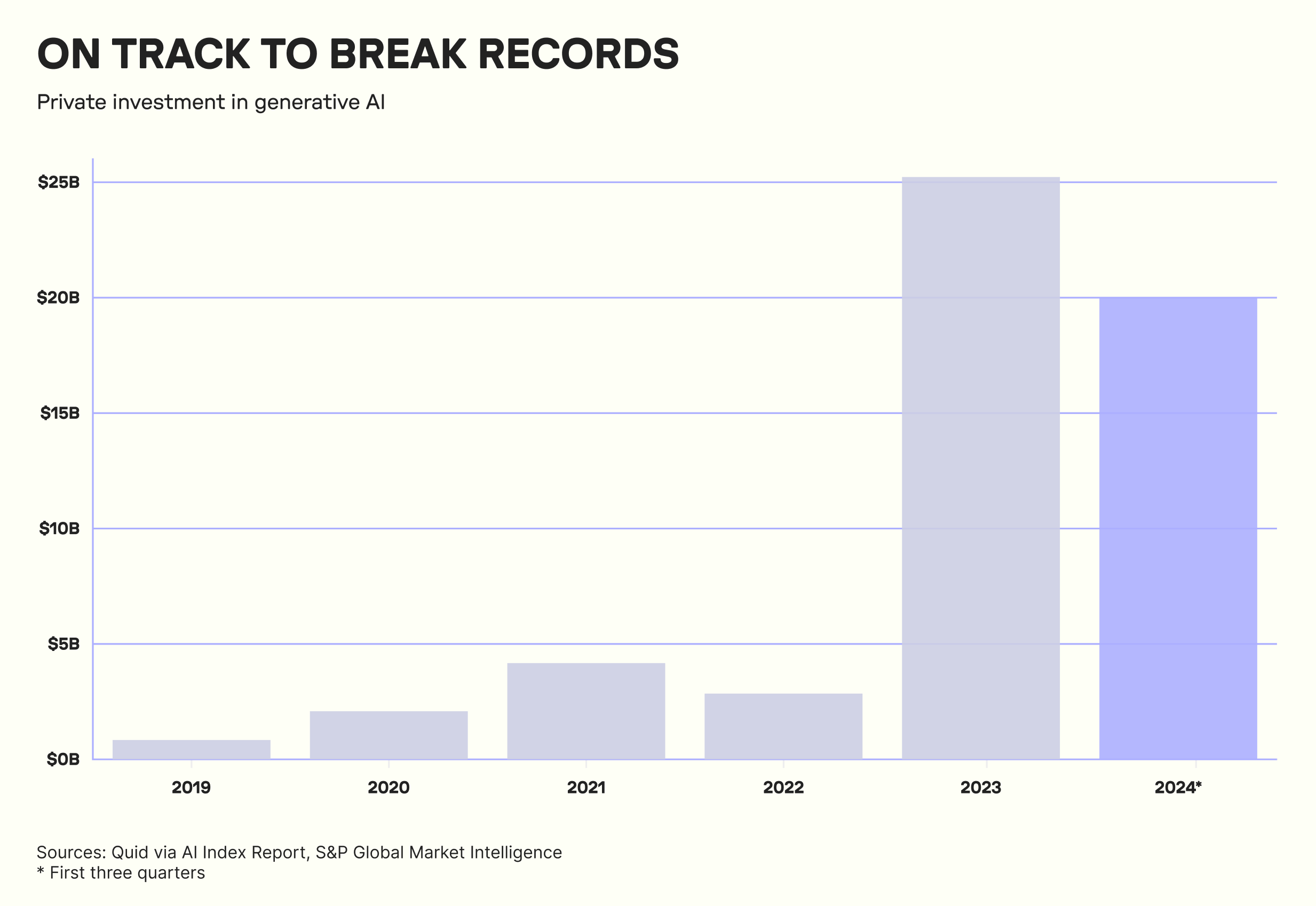

Investment in “AI” from 2010 to 2015, according to CB Insights, totalled less than $1 billion combined, though it did increase dramatically, from $45 million in 2010 to $310 million in 2015.72 Over the 2010s, investment in AI was ongoing, if targeted at “narrow” AI companies aimed at generating production and manufacturing efficiencies—notable startups included Vicarious—but it was a mere fraction of what the boom of 2023 would unleash. According to an OECD report, “between 2015 and 2023, global VC investments in AI start-ups tripled (from USD 31 billion to USD 98 billion), with investments in generative AI specifically growing from 1% of total AI VC investments in 2022 (USD 1.3 billion) to 18.2% (USD 17.8 billion) in 2023, despite cooling capital markets.”73

High-profile investors include Andreessen Horowitz, or a16z, the largest VC firm by assets under management ($42 billion). A16z participated in OpenAI’s $300 million fundraise in April 2023, and has since started a $6 billion fund focused on AI companies and “American dynamism.”74 It has invested in twenty AI startups; according to Pitchbook, “a16z has made a play to own every part of the generative AI value chain.”75 Most notably, it has invested $415 million in a Series A round for French open source AI startup Mistral.

The Valley’s second-largest firm, Sequoia Capital, invested in OpenAI in 2021, and in 2023 also unleashed a blitz of AI investment: $30 million in Collaborative Robotics’ Series A, $28 million in Hex Technologies, $21 million in the legal AI firm Harvey, $15M in CloseFactor, $12.2 million in generative video startup Tavus, $5.5 million in the AI assistant company Dust, $5.3 in Replicate, and $3.2 in Helm, a health AI startup. The firm says it has seventy AI companies in its portfolio.76

THE DREAM OF AGI AND THE FULLY AUTOMATED ORGANIZATION

In sum, OpenAI was likely conceived as a strategic hedge by Elon Musk and Sam Altman against Google’s mounting claim to commercial AI dominance. It was positioned from the start to communicate its altruistic mission contra the for-profit objectives of the tech giants of the day, despite itself being backed by and employed by figures from the largest Silicon Valley firms and venture capital outlets. By deploying the use of “AGI” to elevate its mission beyond the stale concern of generations-old “AI,” it was able to cultivate a cultural mystique that translated into a marketing device that could be wielded to reliably generate press, bolster recruitment of top researchers, and attract investment at crucial corporate junctures.

Thanks to the investment climate and the zero-percent-interest-rate era, there was little concern over a business model being in place as OpenAI’s leadership transitioned into a for-profit—the importance of a strong narrative and the involvement of central Valley figures eclipsed the need for a plan to generate revenue. A precedent had been set by Uber and other “unicorns” that investors and consumers would tolerate long-term efforts to scale and to capture markets. OpenAI was in command of easily the most compelling story about AI, and thus when its product ChatGPT exploded in popularity, it was well poised to capitalize on its recent legacy of presenting itself as a steward of AGI, which the company was itself allegedly developing.

Early competitors like Anthropic would have to compete on grounds of “safety,” but this mattered less as the products reached cultural saturation and market interest became obvious in the generative AI product category, especially from enterprise clients. Now, with widespread industry dedication and investment, and OpenAI successfully at the center of the generative AI economy, a rush to discern what generative AI is actually capable of in a business context unfolded—and continues to unfold even now.

It appears certain that ChatGPT’s rapid, whiplash success was something of a surprise to both the company and its partners. It was not part of a meticulous product roadmap—in fact, OpenAI board member Helen Toner has revealed that the board was not even informed in advance about ChatGPT’s release; They found out, to their chagrin, on Twitter along with everyone else.77 The app quickly notched 100 million users, causing industry analysts at banks and investment firms to swoon. “In 20 years following the internet space, we cannot recall a faster ramp in a consumer internet app,” UBS analysts wrote in a February 2023 report.78

To keep up with demand—especially in server space, given the taxing compute requirements of running AI systems—OpenAI and Microsoft expanded their partnership, with the software giant pledging an additional $10 billion in exchange for the right to use OpenAI technology in its platforms and software offerings, and a cut of OpenAI’s sales.79 (To those keeping track at home, that brought the total to around $13 billion, given past investments and pledges.)

The details of this partnership have not been made public, but it is known to stake much of its value in the form of compute credits for Azure, Microsoft’s cloud compute service.80 It also requires Open AI to use Azure as its compute provider. OpenAI’s embrace of Microsoft—and vice versa—as it moved away from a research organization aimed at “protecting the world from AI” as per the early Altman-Musk iteration, signals the startup’s ambition to take a more capital-intensive approach than Musk was able to offer. There are many reasons why Microsoft might find a deal attractive, and why it’s ideally structured to be tolerant of a startup that has no immediate or obvious roads to profitability. First, since its earliest investments, OpenAI can be seen as a hedge against Google and Facebook, each of which were outspending Microsoft in-house to develop AI systems. Second, the structure of the deal (or what we know of it) ensures that Microsoft will profit from nearly any outcome. Microsoft benefits from using OpenAI’s technology in its products, and receives a cut of revenue from the products OpenAI sells as well—buffering any financial risk, which is already curbed because, as noted above, much of the deal is understood to take the form of compute credits. As such, as recently as the summer of 2024, Microsoft was able to publicly state that it was comfortable with Sam Altman’s vision of an incipient AI, and was not afraid to spend billions investing with no promise of profits in the near term—the deal’s structure, and the dream of AGI, are in ideal symbiosis.

In 2023, after the OpenAI-Microsoft deal was inked, interest in OpenAI, generative AI, and large language models truly exploded. Microsoft added GPT technology to Bing and Copilot; Google announced Bard, which later became Gemini; and Anthropic debuted Claude, its ChatGPT competitor, in March 2023.81 (In Q3 2024, half of all venture capital investment in the US went to AI, up from 15 percent in 2017.82)

OpenAI’s first major move to shape a business model was the obvious one: It opened a premium paid tier for ChatGPT called Plus, offering higher performance for fans and superusers of the app. OpenAI also started granting access to its API, allowing developers and companies to purchase API keys. Within months, the company began leaning into enterprise sales, recognizing the potential in touting an all-powerful technology that could also automate jobs. That spring, OpenAI employees coauthored a report with Cornell researchers about job impacts;83 While the paper was covered in the press as a warning, it had the effect, as many such impact papers do, of bolstering the automation technology’s job-replacing bona fides.

Throughout the rest of 2023, OpenAI floated other ideas for generating revenue, some with more conviction than others. It teased and eventually released an app store for GPT apps developed by independent programmers, as well as the AI video generator Sora. Altman nodded to the idea of selling ads against GPT output online. But the chief potential for revenue generation, and thus the core plank of its business model, remained tied to the same plank: selling enterprise-tier GPTs and selling API access. Now we might see why the AGI mythology is so important to the formulation here: Managers can be assured that they are purchasing both the safest and the most powerful technology available as they seek to cut costs in a tight labor market.

This is similar to the way in which the previous era of tech unicorns—Uber and the gig economy startups—ultimately tried to attain profit by promising to reduce labor costs (in ridehail’s case, by disrupting the taxi and black cab economy) despite the buzzy rhetoric and lofty corporate mythologies. In this case, the talk of AGI supersedes discussions of OpenAI’s enterprise business in the press, making it a more palatable automation company. Reduce tasks, use as leverage, replace jobs, increase attrition.

Nearly two years into the generative AI boom, this still holds true: Enterprise clients, by the company’s own estimation, are the most valuable line of its business by a considerable margin. (OpenAI’s sales figures aren’t public, but many of the major contracts inked so far are.) The largest client of OpenAI is the consulting and financial services firm PwC, which has purchased 101,000 seats.84 The American biotech firm Moderna,85 and Klarna, a Swedish fintech startup, are among other leading users; OpenAI estimated 600,000 total enterprise clients as of the spring of 2024.86 By September, it reported one million.87 In June 2024, the company self-reported its annualized revenue as $3.4 billion.88

Yet OpenAI’s overhead is staggering, making it notably different from the ‘zero price’ products that have otherwise dominated the modern tech industry. Last summer, the company’s compute costs were reported to be $700,000 a day;89 they are certainly much larger now. Sam Altman publicly said he needs $7 trillion in investment for chips to run what he had planned for his AI programs.90 Meanwhile, OpenAI’s workforce is large, expensive, and expanding. Research and development for LLMs requires vast investment, compute, and energy—especially as OpenAI pushes into video production. Licensing deals with media companies for training data have cost the company hundreds of millions of dollars.91 Multiple legal battles, against journalists and creative workers who allege OpenAI has used their work without consent or compensation, are ongoing. And competitors are eating into the company’s market share.

Taken together, we see a portrait of a company that wrapped itself in an altruistic narrative mythology to attract researchers, investment, and press. It stumbled into a hit app that opened a pathway to a new product category in commercial generative AI (something Silicon Valley had been pursuing unsuccessfully for years), ignited a gold rush, drew competitors, and wielded its unique legacy and relationship to AGI to differentiate itself. However, given that generative AI technology is so expensive to develop and run, a unique imperative to generate revenue—lots of revenue—in order to capitalize on its popularity, cultural cachet, and market opportunity has become the company’s dominant concern. (In the past, as mentioned earlier, OpenAI has stated that its move away from nonprofit status was necessitated by the need for more compute power if it were to make satisfactory progress in creating AGI. This can be seen instead as a move toward preparing for an era of commercial product releases, even if the company remained unprepared for the success of ChatGPT when it arrived.) This is how a company transforms from a nonprofit whose aim is to be “owned by all of humanity” and “free of the profit motive” to one whose board is purged of safety experts in favor of Larry Summers.

This frenzy to locate and craft a viable business model has had other consequences. Ongoing and highly unresolved issues regarding copyright threaten the foundation of the industry: If content currently used in AI training models is found to be subject to copyright claims, top VCs investing in AI like Marc Andreessen say it could destroy the nascent industry. Governments, citizens, and civil society advocates have had little time to prepare adequate policies for mitigating misinformation, AI biases, and economic disruptions caused by AI. Furthermore, the haphazard nature of the AI industry’s rise means that by all appearances, another tech bubble is being rapidly inflated.92 So much investment has flowed into the space so fast, based on the bona fides of just a handful of companies—especially OpenAI, Microsoft, Google, and Nvidia—that a crash could prove highly disruptive, and have a ripple effect far beyond Silicon Valley.

This is especially concerning because so much of the business, as we have seen, relies on large enterprise contracts and on using generative AI in a capacity as automation software for creative labor. Given the unreliability, hallucinatory output, and security concerns still posed by even enterprise editions of the software, this makes the long-term gambit of generative AI as efficiency-generating, cost-cutting, and productivity-improving software a deeply dubious one. Goldman Sachs and Sequoia Capital have both authored reports suggesting that generative AI may not be worth the current investment. Sequoia Capital partner David Cahn wrote that the generative AI industry would have to generate $600 billion in revenue annually to sustain the current rate of investment—a long way to go when the biggest company in the space is making $3.4 billion a year.93 Goldman Sachs was even more blunt, finding that there was simply too much spend and too little benefit to justify the technology in most corporate environments.94 The Wall Street Journal reported in July 2024 that firms had switched from discussing generative AI in terms of productivity gains—perhaps in part because those gains were dubious or hard to quantify—to analyzing its capacity for revenue generation.95 If that doesn’t pan out—if companies find generative AI is coming up short on revenue—it’s easy to see a mass dismissal of the technology among corporate firms after the trial periods expire and the hype wears off.

Given that generative AI has entered a new and crucial stage—with large client acquisitions and investor concerns colliding, critics’ voices growing, no new major technology advancements released for months, and a howling imperative to start making money—perhaps it’s no surprise that, once again, OpenAI turned to centering its AGI narrative. In July 2024, OpenAI announced a five-level system for evaluating its technologies on the road to human-level intelligence.96 According to Bloomberg, “the tiers, which OpenAI plans to share with investors and others outside the company, range from the kind of AI available today that can interact in conversational language with people (Level 1) to AI that can do the work of an organization (Level 5).”97 Notably, OpenAI is still at Level 2—its AI is a “reasoner” that can do “human-level problem solving.”

This positioning can be viewed as a resetting of expectations to corporate clients who might be getting itchy after seeing a few months with enterprise GPT fail to provide impressive results, a reminder that AGI is still coming, that the systems are improving all the time—so don’t cancel your contract with us just yet—and a framework through which the company can whet the appetite of future clients. (Note that Altman has had to recalibrate his AGI expectations before; in January 2024, he insisted that AGI is coming, but “will change the world much less than we think,”98 perhaps another effort to tamp down expectations set by, well, himself, just a few months earlier, as corporate clients began to express frustration with the slow gains made by enterprise AI.)

When AGI arrives, OpenAI promises, its AI won’t just be able to do a single worker’s job—it will be able to do all of their jobs. The generative AI on offer at OpenAI’s Level 5 is an “AI that can do the work of an organization.”99 And that, ultimately, is what executives and management are pursuing, and have been pursuing, since the industrial revolution, when early entrepreneurs dreamt up the first fully mechanized factories—completely automated operations producing output for the profit of the one at the helm, without the protests and inefficiencies of a human workforce. In fact, what AGI—artificial general intelligence that can carry out human-level task-making free of human inefficiencies—is to AI researchers, the fully automated factory is to C-suite executives and management consultancies: an ultimate ideal that may or may not be achievable, and yet serves as a powerful driver of interest and investment.

This, perhaps, is also why the apocalyptic nature of the hype around generative AI or a prospective AGI does not seem to have bothered many corporate clients, and why it has instead proven to be such an effective marketing tool. It is in many ways the same dream: a “highly autonomous system that outperforms humans at most economically valuable work.”100 As it turns out, Sam Altman didn’t even have to build his AGI to ask it how it might generate revenue—it was clear from the start.

Acknowledgements

Copyediting by Caren Litherland.

Design by Partner & Partners.

Graph by Roberto Rocha.

Cite as Brian Merchant, “AI Generated Business: The Rise of AGI and the Rush to Find a Working Revenue Model”, AI Now Institute, December 2024.

Footnotes

- “Sam Altman in Conversation with StrictlyVC,” interview by Connie Loizos, YouTube, 53:25, May 18, 2019. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “Nvidia’s Stock Is Expensive. A Look at Why, and How That Should Change, by the Numbers,” Associated Press, June 3, 2024. ↩︎

- Jon Hilsenrath and Ben Leubsdorf, “Fed Raises Rates After Seven Years Near Zero, Expects ‘Gradual’ Tightening Path,” Wall Street Journal, December 16, 2015. ↩︎

- Stephanie Palazzolo and Erin Woo, “OpenAI’s Annualized Revenue Doubles to $3.4 Billion Since Late 2023,” The Information, June 12, 2024. ↩︎

- Cade Metz, “OpenAI Completes Deal That Values Company at $157 Billion,” New York Times, October 2, 2024. ↩︎

- “Anthropic Forecasts More than $850 Mln in Annualized Revenue Rate by 2024-End – Report,” Reuters, December 26, 2023. ↩︎

- Steven Levy, “How Elon Musk and Y Combinator Plan to Stop Computers From Taking Over,” Medium, December 11, 2015. ↩︎

- Ina Fried, “OpenAI Raises $6.6 billion in largest VC round ever.” Axios, October 2, 2024. ↩︎

- “Superintelligence on NYT Bestseller List,” Future of Humanity Institute, University of Oxford, August 18, 2024. ↩︎

- Ashlee Vance, Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future (New York: Ecco Press, 2015). ↩︎

- See Cade Metz, Karen Weise, Nico Grant, and Mike Isaac, “Ego, Fear and Money: How the A.I. Fuse Was Lit,” New York Times, December 3, 2023. ↩︎

- See Walter Isaacson, “Inside Elon Musk’s Struggle for the Future of AI,” Time, September 6, 2023; and Metz, Weise, Grant, and Isaac, “Ego, Fear and Money.” ↩︎

- Isaacson, “Inside Elon Musk’s Struggle for the Future of AI.” ↩︎

- Kai Xiang Teo, “Musk Once Tried to Stop Google’s DeepMind Acquisition in 2014, Saying the Future of AI Shouldn’t Be Controlled by Larry Page,” Yahoo News, September 7, 2023. ↩︎

- Catherine Shu, “Google Acquires Artificial Intelligence Startup DeepMind for More than $500M,” TechCrunch, January 26, 2014. ↩︎

- Samuel Gibbs, “Elon Musk: Artificial Intelligence Is Our Biggest Existential Threat,” Guardian, October 27, 2014. ↩︎

- Sam Altman, “Machine Intelligence, Part 1,” February 25, 2015. ↩︎

- Nick Robins-Early, “The Feud Between Elon Musk and Sam Altman – Explained,” Guardian, March 9, 2024. ↩︎

- Samuel Gibbs, “Musk, Wozniak and Hawking Urge Ban on Warfare AI and Autonomous Weapons,” Guardian, July 27, 2015 ↩︎

- “OpenAI and Elon Musk,” OpenAI, March 5, 2024. ↩︎

- “Introducing OpenAI,” OpenAI, December 11, 2015. ↩︎

- Jillian D’Onfro, “Google’s CEO Is Looking to the Next Big Thing Beyond Smartphones,” Business Insider, April 21, 2016. ↩︎

- Karen Hao, “We Read the Paper That Forced Timnit Gebru out of Google. Here’s What It Says,” MIT Technology Review, December 4, 2020. ↩︎

- Jon Brodkin, “Google Fires Blake Lemoine, the Engineer Who Claimed AI Chatbot Is a Person,” Ars Technica, July 25, 2022. ↩︎

- Richard Nieva, Alex Konrad and Kenrick Cai, “‘AI First’ to Last: How Google Fell Behind in the AI Boom,” Forbes, February 9, 2023. ↩︎

- Nick Statt, “Google Now Says Controversial AI Voice Calling System Will Identify Itself to Humans,” Verge, May 10, 2108 ↩︎

- “Open AI and Elon Musk.” ↩︎

- “Introducing OpenAI.” ↩︎

- Though the dollar amounts have not been made public, Musk is understood to be the largest and most important initial donor, with reported funding in the $45 million to “hundreds of millions” range. ↩︎

- “Introducing OpenAI.” ↩︎

- Russell Brandom, “Elon Musk and Partners Form Nonprofit to Stop AI from Ruining the World,” Verge, December 11, 2015. ↩︎

- “Tech Giants Pledge $1Bn for ‘Altruistic AI’ Venture, OpenAI,” BBC, December 12, 2015. ↩︎

- Emily Jane Fox, “Sam Altman on His Plan to Keep A.I. out of the Hands of the ‘Bad Guys’,” Vanity Fair, December 15, 2015. ↩︎

- See Leslie Hook, “Silicon Valley in Move to Keep AI Safe,” Financial Times, December 11, 2015. ↩︎

- Levy, “How Elon Musk and Y Combinator Plan to Stop Computers from Taking Over.” ↩︎

- More recently, an OpenAI representative gave a demo where he claimed that Sora is an important stepping stone on the road to AGI, because in order to create good videos of people, you have to know how people think. ↩︎

- Pierre-Yves Oudeyer, “The Lighthill Debate on Artificial Intelligence: ‘The General Purpose Robot Is a Mirage’,” YouTube, 1:23:11, March 7, 2018. ↩︎

- Jeffrey Funk and Gary Smith, “Why A.I. Moonshots Miss,” Slate, May 4, 2021. ↩︎

- See Emily M. Bender, “Opening Remarks on ‘AI in the Workplace: New Crisis or Longstanding Challenge’,” Medium, October 1, 2023. ↩︎

- Mark Gubrud (@mgubrud), “This is the original (first published) definition of AGI. It was not a pejorative against anything. It was an attempt to set a milestone for future AI that would have qualitatively distinct (from then-AI) impacts esp. re international security,” Twitter (now X), July 25, 2019. ↩︎

- David Deutsch, “Philosophy Will Be the Key That Unlocks Artificial Intelligence,” Guardian, October 3, 2012. ↩︎

- “Introducing OpenAI.” My emphasis. ↩︎

- “OpenAI Technical Goals,” OpenAI, June 20, 2016. My emphasis. ↩︎

- “OpenAI and Microsoft,” OpenAI, November 15, 2016. My emphasis. ↩︎

- “OpenAI and Elon Musk.” ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “OpenAI Supporters,” OpenAI, February 20, 2018. ↩︎

- “OpenAI Charter,” OpenAI, April 9, 2018; accessed November 1, 2024. My emphasis. ↩︎

- “Improving Language Understanding with Unsupervised Learning,” OpenAI, June 11, 2018. ↩︎

- Tom Simonite, “The AI Text Generator That’s Too Dangerous to Make Public,” Wired, February 14, 2019. ↩︎

- “OpenAI LP,” OpenAI, March 11, 2019. ↩︎

- Ibid. My emphasis. ↩︎

- “Microsoft Invests in and Partners with OpenAI to Support Us Building Beneficial AGI,” OpenAI, July 22, 2019. My emphasis. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “Organizational Update from OpenAI,” OpenAI, December 29, 2020. ↩︎

- “DALL-E: Creating Images from Text,” OpenAI, January 5, 2021. ↩︎

- “Anthropic: An AI Safety and Research Company That’s Working to Build Reliable, Interpretable, and Steerable AI Systems,” Welcome AI, May 2021, accessed November 1, 2024. ↩︎

- “Anthropic Raises $124 Million to Build More Reliable, General AI Systems,” Anthropic, May 28, 2021. ↩︎

- This might be seen as what will become something of an “AI safety” arms race, in which new entrants compete to declare their product the safest vehicle for achieving AI. For the culmination of this trend, see Ilya Sutskever, Daniel Gross, and Daniel Levy, Safe Superintelligence Inc., June 19, 2024, accessed November 1, 2024. ↩︎

- Cade Metz, “Meet DALL-E, the A.I. That Draws Anything at Your Command,” New York Times, April 6, 2022. ↩︎

- For examples, complete with adulatory headlines, see Casey Newton, “How DALL-E Could Power a Creative Revolution,” Verge, June 10, 2022; and Mark Sullivan, “OpenAI’s DALL-E AI Is Becoming a Scary-Good Graphic Artist,” Fast Company, April 6, 2022. ↩︎

- “Introducing ChatGPT,” OpenAI, November 30, 2022. ↩︎

- Kevin Roose, “The Brilliance and Weirdness of ChatGPT,” New York Times, December 5, 2022. ↩︎

- Cade Metz and Karen Weise, “Microsoft to Invest $10 Billion in OpenAI, the Creator of ChatGPT,” New York Times, January 23, 2023. ↩︎

- See Chloe Xiang, “Microsoft Now Claims GPT-4 Shows ‘Sparks’ of General Intelligence,” Motherboard, March 24, 2023; and Sébastien Bubeck, Varun Chandrasekaran, Ronen Eldan, Johannes Gehrke, Eric Horvitz, Ece Kamar, Peter Lee, Yin Tat Lee, Yuanzhi Li, Scott Lundberg, Harsha Nori, Hamid Palangi, Marco Tulio Ribeiro, and Yi Zhang, “Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence: Early Experiments with GPT-4,” arXiv, March 22, 2023. ↩︎

- Sarah Krouse, Deepa Seetharaman, and Joe Flint, “Behind the Scenes of Scarlett Johansson’s Battle With OpenAI,” Wall Street Journal, May 23, 2024. ↩︎

- “OpenAI Board Forms Safety and Security Committee,” OpenAI, May 28, 2024. ↩︎

- “MavenAGI Launches Automated Customer Support Agents Powered by OpenAI,” OpenAI, n.d., accessed November 1, 2024. ↩︎

- “OpenAI Charter.” My emphasis. ↩︎

- “Deep Interest in AI: New High in Deals to Artificial Intelligence Startups in Q4 ’15,” CB Insights, February 4, 2016. ↩︎

- Celine Caira, “The Future of Artificial Intelligence,” in OECD Digital Economy Outlook 2024 (Volume 1): Embracing the Technology Frontier, OECD, 2024. ↩︎

- Sam Blum, “A16z Targets AI as Part of New $6 Billion Fund, Days After Marc Andreessen Called OpenAI’s Security Protocol ‘Swiss Cheese’,” Inc., March 7, 2024. ↩︎

- Jacob Robbins, “Andreessen Horowitz’s $415M Mistral investment Rounds Out AI Strategy,” PitchBook, December 10, 2023. ↩︎

- Gené Teare, “Inside Sequoia Capital’s Growing AI Portfolio,” Crunchbase News, October 23, 2023. ↩︎

- Helen Toner, interview by Bilawal Sidhu, The TED AI Show, May 2024. ↩︎

- Krystal Hu, “ChatGPT Sets Record for Fastest-Growing User Base – Analyst Note,” Reuters, February 2, 2023. ↩︎

- “Microsoft and OpenAI Extend Partnership,” Microsoft (blog), January 23, 2023. ↩︎

- Zitron, Ed. “How Does Open AI Survive?” Newsletter, July 29, 2024. ↩︎

- “Introducing Claude,” Anthropic, March 14, 2023. ↩︎

- Rani Molla, “Watch AI Eat the VC World in One Chart,” Sherwood News, July 17, 2024 ↩︎

- Tyna Eloundou, Sam Manning, Pamela Mishkin, and Daniel Rock, “GPTs Are GPTs: An Early Look at the Labor Market Impact Potential of Large Language Models,” arXiv, March 17, 2023. ↩︎

- “PwC to Become OpenAI’s Largest Enterprise Customer amid genAI Boom,” Reuters, May 29, 2024. ↩︎

- “Accelerating the Development of Life-Saving Treatments,” OpenAI, n.d., accessed November 1, 2024. ↩︎

- Jackie Davalos, “OpenAI Sees ‘Tremendous Growth’ in Corporate Version of ChatGPT,” Bloomberg, April 4, 2024. ↩︎

- “OpenAI Hits More than 1 Million Paid Business Users,” Reuters, September 5, 2024. ↩︎

- Palazzolo and Woo, “OpenAI’s Annualized Revenue Doubles to $3.4 Billion Since Late 2023.” ↩︎

- Aaron Mok, “ChatGPT Could Cost over $700,000 per Day to Operate. Microsoft Is Reportedly Trying to Make It Cheaper,” Business Insider, April 20, 2023. ↩︎

- Keach Hagey, “Sam Altman Seeks Trillions of Dollars to Reshape Business of Chips and AI,” Wall Street Journal, February 8, 2024. ↩︎

- The licensing deal with NewsCorp alone was worth $250 million. See, e.g., Alexandra Bruell, Schechner, and Deepa Seetharaman, “OpenAI, WSJ Owner News Corp Strike Content Deal Valued at over $250 Million,” Wall Street Journal, May 22, 2024. ↩︎

- Sam Blum, “Warnings About an AI Bubble Are Growing. When Could It Burst?” Inc., July 10, 2024. ↩︎

- David Cahn, “AI’s $600B Question,” Sequoia Capital, June 20, 2024. ↩︎

- “Gen AI: Too Much Spend, Too Little Benefit?” Goldman Sachs, June 27, 2024. ↩︎

- Isabelle Bousquette, “It’s Time for AI to Start Making Money for Businesses. Can It?” Wall Street Journal, July 10, 2024. ↩︎

- Rachel Metz, “OpenAI Scale Ranks Progress Toward ‘Human-Level’ Problem Solving,” Bloomberg, July 11, 2024. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- MacKenzie Sigalos and Ryan Browne, “OpenAI’s Sam Altman Says Human-Level AI Is Coming but Will Change World Much Less than We Think,” CNBC, January 16, 2024. ↩︎

- Metz, “OpenAI Scale Ranks Progress Toward ‘Human-Level’ Problem Solving.” ↩︎

- “OpenAI Charter.” ↩︎